It’s summertime — and when I think of summer, I suddenly want to drink a glass of lemonade, stop by Dairy Queen for ice cream, and watch a baseball game.

Ah, baseball…

I probably can’t name a baseball player from the last decade (not a lot of baseball coverage here in London), but I LOVE stories about baseball.

And this week I’m bringing you a fun one that mixes underdogs, creativity, and mavericks.

[Editor’s Note: You do not need to like baseball or sports to enjoy this story. I love the stories I share here, and try not to pick favorites. But I’ll say it, I really love this one.]

It’s about a minor league player who became an actor and later decided to start a minor league team — hiring all the guys the major league teams wouldn’t.

What would happen?

I was curious…

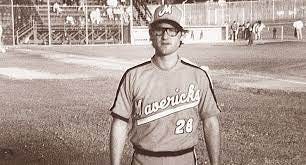

This is the story of Bing Russell and the Portland Mavericks.

Growing up in the 1930s and 1940s, Neil “Bing” Russell was the spring training errand boy for the New York Yankees, chasing after the greats like Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Lefty Gomez.

After he graduated from Dartmouth with a degree in business administration, Bing set out to become a professional ball player.

Lefty Gomez, then a scout, signed him to a Yankee contract, but after four years playing in the minors in Alabama and Georgia, Bing’s baseball career ended abruptly – after he was rammed in the forehead by a fastball.

“I was in a daze from August 16 to November 25,” Bing said.

“It was the only truly sad thing that’s ever happened to me.”

With his career as a ballplayer over, Bing decided to try his hand at acting.

In 1952, he talked his way into his first motion picture – The Big Leaguer – playing the umpire, and soon after moved to California with his wife and young children.

He found steady work as a character actor throughout the 1950s and 1960s, mostly in TV Westerns and crime dramas.

Then he landed the role of Deputy Clem Foster on the popular TV show Bonanza, a role he would play for 13 years.

But in 1973, Bonanza ended.

Bing was now a middle-aged man, and the acting roles were drying up.

That’s when Bing’s son – Kurt (yes, that Kurt Russell) – had an idea for his old man.

Bing had raised his kids on baseball, schooling them with long written exams on baseball strategy and fielding grounders in a room in their home.

The 24-year-old Kurt had an acting contract with Disney, but was also a skilled ball player who loved the game like his father, and had played in the minor leagues.

Kurt told his father that Portland’s longtime Triple-A team, the Beavers, were leaving their Oregon home.

Organized baseball had given up on Portland as a home for a baseball team.

But Kurt – and Bing – saw an opportunity.

Bing had grown up at a time when professional baseball had hundreds of independent teams across the country.

Now the minor league teams were all affiliated with a Major League franchise, and players moved around all the time.

Ball players were no longer part of a community – and with constant changes, fans never knew who their pitcher or catcher or outfielders were going to be.

Bing saw what this was doing to the sport he loved – and he had an opportunity to do something about it.

“I am terribly old fashioned and I love the game dearly,” he told the Los Angeles Times.

He wanted to take baseball back to what he called “the straw hat and beer days” when there were hundreds of unaffiliated teams and leagues across the country.

“An independent team has that certain traditional charm with older players and those with local charisma.”

“I felt there were plenty of ballplayers around, rejects or those overlooked by major league teams, who could still compete.”

So he paid $500, and bought a franchise.

The Portland Mavericks were born.

In 1973, Portland, Oregon was a struggling blue-collar town.

The real estate was cheap, the job opportunities were few, and the downtown had been ridiculed for its “bomb-site look” by the New York Times.

In short, Portland was an underdog.

Just like Bing Russell.

Major League Baseball didn’t have any faith in the Mavericks or Portland as a baseball city – and Bing was determined to prove them wrong.

And Bing’s new team wouldn’t be anything like the Portland Beavers.

His Mavericks were now the only independent minor-league baseball team in the country.

That meant he didn’t have any Major League money to spend. But he also didn’t have the Major League rules.

While most of the baseball talent was scouted and signed to the Major League teams, Bing decided to use a different approach.

He put an ad in the paper – and ran open tryouts.

“Don’t you see?” Bing asked.

“It’s the American dream. It’s a matter of opportunity, not the almighty dollar.”

Hundreds of hopefuls traveled to Portland “by plane, bus, car and thumb” to take one more shot at playing professional baseball.

Think of it like Field of Dreams, with a sea of ball players whose major-league careers were cut short, or never happened.

“The Mavs were the Last Chance Saloon kind of thing,” said Rob Nelson, a pitcher for the Mavericks.

“Most of us knew this was it for us in baseball. It was summer camp for us.”

The Mavericks weren’t polished like other ball players. Many were older, in their 30s, and were savoring their last chance to play professionally.

“Most of the Mavericks had a bit of a paunch,” said Rob Nelson.

“They led the league in stubble.”

The Mavs were just a group of guys who loved the game – and knew too well the joy and pain that came with loving baseball.

And without the constraints of Major League Baseball, the Mavericks were able to be….well, mavericks.

Though they knew how to play fundamental baseball, Bing and the Mavs emphasized something many other teams were missing –

FUN.

“We really emphasized fun,” Nelson said.

Bing made some unusual choices, like keeping a ridiculously large roster, even though that meant some of those extra players spent far more time bartending than running bases or catching fly balls.

“Never know when you might need an extra man,” Bing told reporters when asked about the expanded list of players.

Rob Nelson understood what that was really all about.

“Bing wanted guys to be able to sit in a bar and tell a girl, ‘Yeah, I play pro ball,’” he said.

“He wanted them to feel important.”

“He was colorful.”

“But most of all, he was kind. Really kind.”

But could a bunch of has-beens focused on fun as much as the fundamentals actually win?

In their first game, they found out – pitching a no-hitter, and winning the game.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘This is going to be magic. This is going to be magic,’” remembered Kurt Russell, who was playing for the team.

And to everyone’s surprise, the Mavs kept winning.

They stole bases. They took chances. And they were relentless.

They wanted to beat the organized franchises – and they did.

Bing’s achievements with the Mavericks saw him named the Class A executive of the year in 1974, an award that was presented to him by Lefty Gomez.

The Mavericks atmosphere of fun and a culture of underdogs was something that the press and baseball fans loved.

And the city of Portland – bruised by the rejection from Major League Baseball – embraced them.

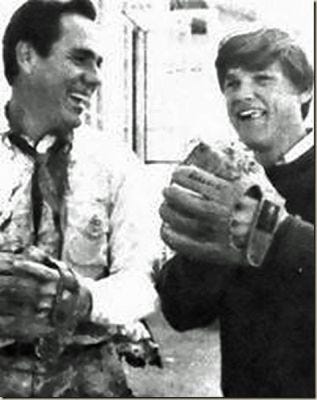

The press attention caught the attention of Jim Bouton, a 38-year-old former Yankees star.

Bouton was in the doghouse with Major League Baseball after publishing Ball Four, a tell-all book about baseball.

No one wanted him on their team, but Bing welcomed him to the Mavericks.

The pay was a meagre $400/month, but Bouton wanted in.

“Our motive was simple,” Jim Bouton said.

“Revenge.”

And with a major league talent like Bouton now on the roster, the Mavs were even more of a draw.

They were setting attendance records, having fun, and they were winning.

“It’s great,” said Mavs shortstop Steve Collette.

“We’re envious of the organization teams, and we want to show them we don’t have to play by the book to win.”

The Mavs won four division titles in five seasons and created a loyal, enthusiastic fan base – all without the support of Major League Baseball.

They were a great underdog success story, but not everyone was a fan.

Especially Major League Baseball.

With the Mavericks, Bing had proven that Portland could support a franchise – and baseball’s suits did not like seeing him succeed where they had failed.

Major League Baseball owned the territory – and decided to bring the Beavers back to Portland.

After the 1977 season, Bing was offered $26,000 by the Pacific Coast League, five times the usual payout for the lower league territory.

Bing was insulted, and said they needed to put a zero between the two and the six – an amount that seemed outrageous to suggest.

Instead of going away quietly, Bing forced an arbitration proceeding – and insisted on testifying.

“He was Jimmy Stewart playing Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” wrote Jack Faust, Bing’s lawyer and friend.

Bing argued the case was not about money – it was about “the soul of a city.”

And Bing won his case – and was awarded the staggering $206,000 he had asked for.

But he also lost.

The Mavericks were officially done.

“He loved owning the Mavericks. It was a tragedy for him to lose the team,” Jack Faust said.

“Those were his happiest days, running that team.”

“My dad was a serious baseball guy who knew how to marry business and baseball and entertainment,” said Bing’s son Kurt.

“That was his gift. And one of the reasons he made money was because he didn’t sell pantyhose at second base. He sold baseball to the people of the town. It’s a big difference.

“And he understood entertainment, that entertainment comes from good competition and winning.”

The Mavericks’ time in Portland may have been cut short, but they certainly left their mark on the town – and on baseball.

Bing said it best, talking about what he and the Mavericks did in a 1976 interview:

“I wanted to show the world we could start $50,000 behind [the amount teams provide farm clubs] and survive.

“Even better, that we could operate in the black. That we could fight city hall and win.

“By God, we did it all and more. It’s incredible.”

One more thing…

Bing Russell’s time as a baseball player and owner may have ended in 1977 – but there was one more chapter in his baseball story.

In 1987, Bing’s grandson Matt Franco – a former batboy for the Mavs – was drafted by Major League Baseball out of high school.

And Matt’s biggest fan was his grandfather.

“He'd bring my grandma and they’d get an apartment wherever I was playing, follow the buses, drive hundreds of thousands of miles, and didn't miss a game from my second year all the way through Triple A,” Matt said.

“If I played 1,500 games in the minors, they probably saw 1,400.”

And unlike his grandfather and uncle, Matt made it to the Majors, debuting with the Chicago Cubs in 1995, and later playing for the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves.

“When I got to the big leagues, they said they could see the games better on TV.”

But wait, there’s more!

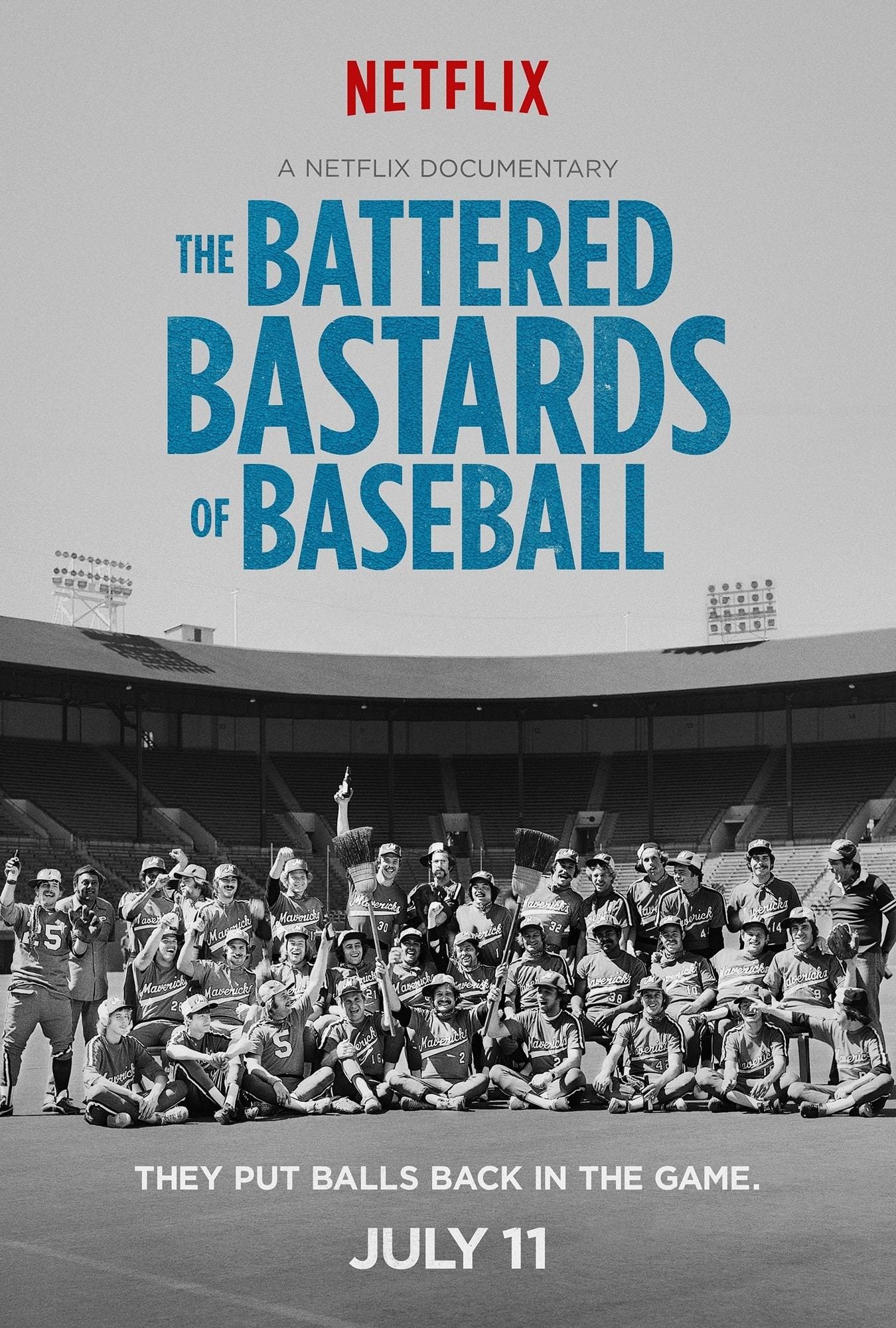

There’s a lot more to the story (involving batboys who would become Academy Award winning filmmakers and the creation of a baseball-inspired bubble gum), and if you’re curious, I highly recommend the 2014 documentary, The Battered Bastards of Baseball, written and directed by Bing’s grandsons Chapman and Maclain Way.

Recent Work and Writing

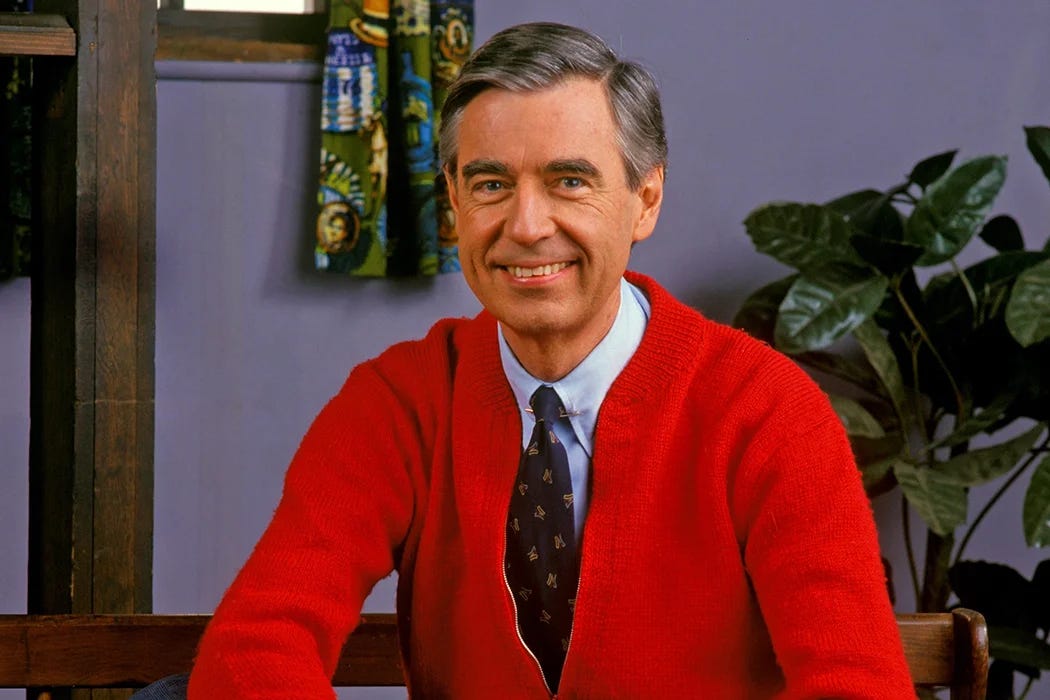

The Helpers Are Out There — Mr. Rogers was right. The world is not as bleak as the news might have you believe.

I Wish I’d Learned This in College — There was no course that prepared me for this…

Ask Better Questions: Five Tips to Help You —Asking a question clearly and succinctly is a skill. Here are five tips to help you master it.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

This week we saw the CEO of CNN, Chris Licht, lose his job — just five days after The Atlantic published a devastating profile of his time at CNN. And there are plenty of communication lessons from his story, too.

And how about these two hot shot lawyers?

Their words (racist, sexist, and all kinds of offensive) have sunk their careers and their reputations.

Just more reminders that communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, Stay Curious!

-Beth