Hello friends!

Do you ever hear those stories about people who fall off cruise ships late at night (usually after a few-too-many tropical cocktails) and live to tell the tale?

Think about it: someone falls off a ship in the dark night, and they survive not just the fall, but also hours in the vast ocean alone — as the cruise ship continues on its journey, completely unaware that someone fell off the Lido deck.

When I read about a 28-year-old man named James Michael Grimes who fell off a cruise ship last November, I couldn’t believe he survived.

The cruise ship was on its way to Cozumel when James fell overboard. It was late at night, and no one saw him fall. His family didn’t know he was missing until the next day.

When the cruise ship officials notified the Coast Guard, James hadn’t been seen in 14 hours.

But miraculously, after spending 20 hours in the water, he was rescued.

How in the world did the Coast Guard find him?

It’s one thing to rescue someone after they report their position, but when people like James fall into the open water, how does the Coast Guard actually find them?

I was curious…

One reason the US Coast Guard can rescue more people today is because of unsung heroes like Arthur (Art) Allen.

Art spent more than 35 years with the US Coast Guard, working as their sole oceanographer.

During that time, Art was focused on solving one problem – how to improve Coast Guard Search and Rescue.

When Art began his career, Art said search and rescue focused on answering two questions:

How do we search?

Where should we look?

Art was tasked with answering the second question.

He spent many years finding better ways to measure wind and ocean currents to determine where a floating object might go.

He also recognized that search and rescue would be hampered if people didn’t understand how objects would drift.

He spent years gathering research and conducting experiments to learn more about leeway drift.

In 1999, he published his findings in a 351-page report titled Review of Leeway: Field Experiments and Implementation.

In the report, he organized the data from 25 field studies, reviewing the test objects and methods used to measure leeway. He also presented a new model for predicting leeway drift that took advantage of better data that was now available.

In May 2001, Art was invited to leave his cubicle in Connecticut and observe a search and rescue team in Virginia.

He saw first-hand how the Coast Guard’s search and rescue operations worked – and on that day, a weather event in the Chesapeake Bay triggered several distress and rescue calls.

“The search and rescue operator was dispatching helicopters and cutters as fast as he could, and saving one person after another,” Art said.

“But he had only a crude computer tool, and was having to make a lot of calculations by hand.”

After Art had observed the operations for the better part of a day, a call came in that another sailboat was missing – along with its passengers, three adults and one child.

The Coast Guard had details of the sailboat’s plans for the day, but their program didn’t allow the operator to input the information.

There was no data available on the winds over the water, or reading of the tides in the bay.

The operator was trying to locate the boat using equations from a 40-year-old study – and he did not have drift equations for the type of boat they were looking for.

“I could see he couldn’t adequately plan the search,” Art said.

“The tool he’d been given could not help him do what he needed to do.

“And so the Coast Guard went looking for something without any real idea of where it was.

Though helicopters and an 87-foot cutter searched through the night, they found nothing.

“Not until the following morning did the sailboat appear, upside down, a long way from where the Coast Guard had been searching.”

Two of the passengers survived. But a mother and her young daughter did not.

Art recognized that the mother and daughter had not been rescued because no one knew how they would drift.

He knew that the Coast Guard didn’t have an adequate tool for search and rescue — and he was inspired to create one.

Art conducted more field experiments, throwing objects in the ocean and studying where they’d move.

He recognized that people didn’t always drift with the current, and how life rafts, surfboards, kayaks, and skiffs drifted differently.

He then created a tool that would grab real-time ocean currents and wind speed faster than the Coast Guard’s existing tool. Additionally, Art’s tool would calculate drift – an important feature that the current tool did not offer.

By 2007, Art had created mathematical equations to describe the drift of 68 different objects — and his work paved the way for improved search and rescue policies and a planning system used by the US Coast Guard.

Thanks to Art’s research, the Coast Guard can now search for more than 100 search objects. His work narrows down the search and rescue area, and that saves the Coast Guard both time and money.

And more importantly, it saves lives.

It’s something that isn’t lost on him.

In a podcast interview, Art audibly choked up talking about the passion of the search and rescue world.

“You’re saving the lives of the most desperate people.

“We’re literally pulling people out of the water that would be dead within hours.

“Our helicopter crews and the air crews, they’re all heroes - [It’s] a very difficult job and they deserve all the credit they get.”

But Art downplays his life’s work, noting that while he contributed, the progress was the result of a team of collaborators.

“It may be my algorithms, a lot of my ideas and the things I prototyped and demonstrated, but it’s not my code that is in the field.”

While Art’s role in saving lives may be behind the scenes, others know the value of his contribution, including Jennifer Conklin, a search and rescue specialist who worked with Art for more than a decade.

“It is always our helicopter and boat crews that get the lifesaving medals, the awards and pictures in the paper,” she said.

“But the guy who makes sure those people get there to save the lives is Art.”

Recent Work and Writing

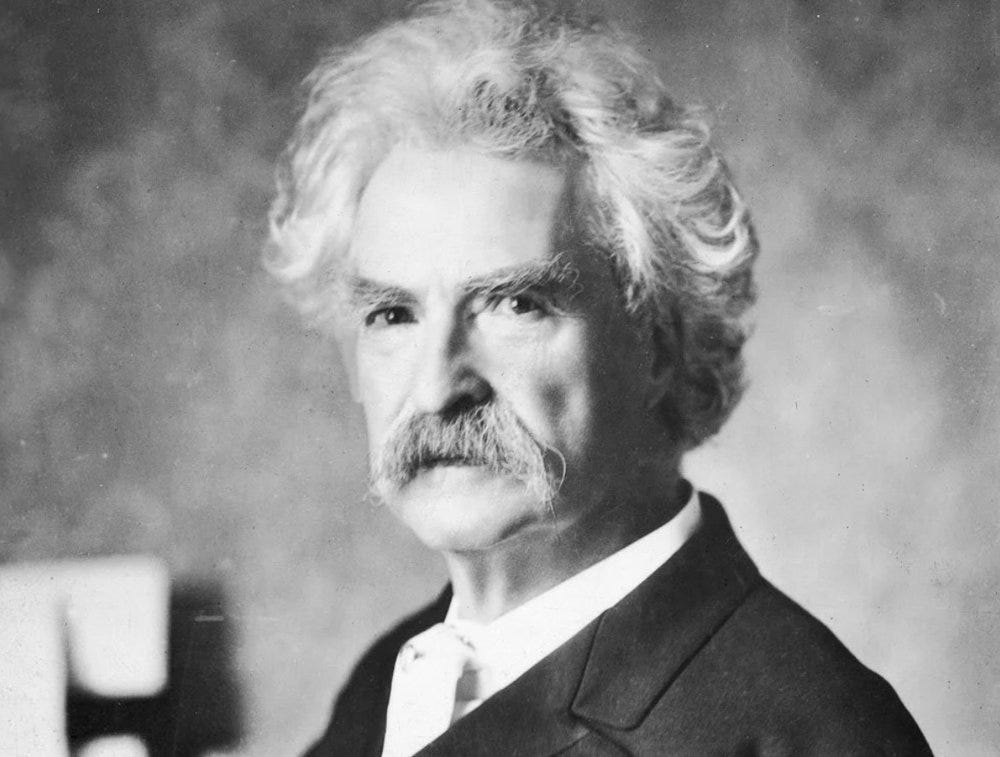

How Mark Twain Can Make You a Stronger Communicator — The Right Word Can Make Your Message Perfect.

One Communication Skill to Build in 2023 — It’s an underrated skill, but also a valuable one.

Work with Women? — Here’s something you should know.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, stay curious!

-Beth

Great piece!