Happy International Women’s Day!

Today I’m sharing a bonus longer read to celebrate International Women’s Day.

This may seem different from my usual writing, but true to the name of this newsletter, it began with curiosity.

Over a year ago, I read an article about a journalist named Melissa Ludtke, and I was so curious about her story - and how she fought Major League Baseball in the name of all female journalists.

She generously shared her story with me.

Here’s what I learned.

Melissa Ludtke wasn’t trying to change the world.

She was just trying to do her job.

As a young girl growing up in a Massachusetts college town in the 1950s and 60s, Melissa was always playing a sport – from volleyball and basketball to tennis and sailing.

But the opportunities for girls were different then – and so were the sports.

“When we were taught basketball, we had to dribble the ball three times and then to pass it,” she told me.

“They made these rules so that we didn’t ‘overexert’ ourselves.”

“The games were tediously slow and not a lot of fun to watch. But the way we were told to play basketball was analogous to how we lived our lives as girls in those days.”

Melissa never dreamed she’d one day be living in New York City, working for Sports Illustrated, and meeting some of the sports legends she had grown up admiring.

But a chance meeting in the summer of 1973 changed the course of Melissa’s life.

“I was staying in Cape Cod the summer after college graduation, and was invited to a friend’s house for dinner. [Famous sportscaster and football legend] Frank Gifford was there, seated across the table from me. We got to talking about sports – and at the end of dinner he said to me, in a very complimentary way, ‘For a girl, you know a lot about sports.’”

This chance meeting had Melissa soon driving her dad’s olive green Pinto wagon to New York City – and meeting Gifford at ABC Sports, where he was a sportscaster on Monday Night Football.

Gifford was ‘very generous’ and took Melissa around and introduced her to others. After three days in New York, she returned to Cape Cod and was determined to get a job at ABC Sports.

So she moved to New York City.

With a monthly ABC Sports work schedule in hand (thanks to her roommate, who was a production assistant there), Melissa would ‘just show up’ – making herself available for any opportunity that would come her way.

Often she worked for free, and when she signed up as a ‘go for’ she was paid $25/day to run errands or complete tasks for the broadcasters and producers at ABC Sports. She met people she admired, like tennis player Billie Jean King and swimmer Donna de Varona.

But for a woman at that time, there weren’t many career opportunities in journalism or television.

“I was afraid I’d have to be a secretary,” she said. “My stenography was terrible, but my typing was pretty good.”

After she took the secretarial test, one of the vice-presidents at ABC Sports held her test results in one hand and her resumé in the other.

He noticed that Melissa had graduated from Wellesley College.

“I don’t think you want to be a secretary,” he said.

She didn’t get the job.

But she did manage to get a job as a secretary at Harper’s Bazaar, and when she wasn’t working there, she ‘hung out at ABC Sports’ as much as she could.

She was willing to pay her dues and help out however she could, so if a producer asked her to run to a local bar and return with martinis for prominent sports journalist Howard Cosell, she did.

A producer noticed her work ethic and drive – and one day said to her, ‘I know someone at Sports Illustrated…”

That introduction helped Melissa land an interview with Sports Illustrated – but not a job.

“I was competing against people who had been editors at their college newspapers; against Princeton boys,” she said. “I had a degree in art history. It was not an easy sell.”

Melissa received a rejection letter – and hung it on her wall.

And she persisted.

She continued to help out with ABC Sports, and kept in contact with the man who had interviewed – and rejected – her at Sports Illustrated.

“I’d let him know what I was doing,” she said, “like when I was at Mamaroneck [New York] at the US Golf Open, at the 18th hole with [British golf journalist] Henry Longhurst.”

She sent her Sports Illustrated interviewer a postcard from the 18th hole – and ‘just kept in touch.’

The postcards (and Melissa’s tenacity) made an impression, and a few months later she was invited to come back for another interview at Sports Illustrated.

This time, she got the job.

“You have opportunities that come along in life.

Prepare to act on them.”

Melissa was hired as a researcher/reporter assigned to help with the TV/radio column.

But she was determined to work on baseball, and strategized and worked hard for more than a year to make it happen.

She volunteered to do the ‘baseball books’ – a thankless task that involved going through all of the newspapers to track every box score and prepare stat sheets each week for the baseball writer.

“It was a lot of work. I willingly took it on even though I was assigned to other things, because I really wanted baseball,” she said. “I paid my dues.”

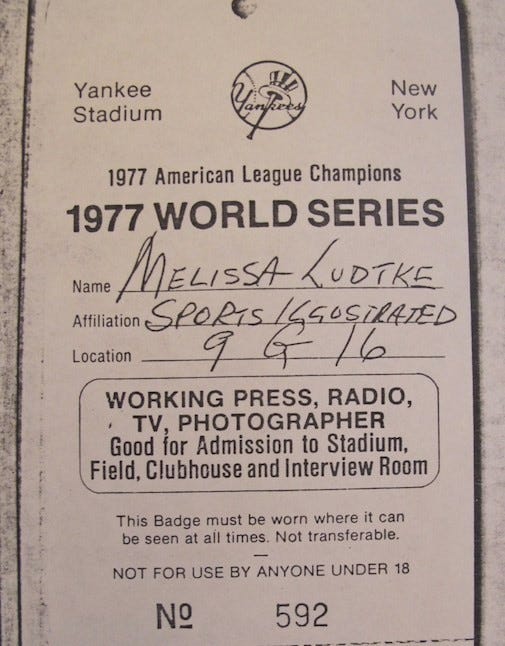

Once she was assigned to the baseball beat, she took advantage of the press passes she was given, attending as many games as she could.

And she learned along the way.

She was also fortunate to have generous and supportive colleagues – including writer Bill Leggett and editor Patricia Ryan – who encouraged her to hone her writing and reporting skills.

Then the 1977 World Series began.

NY Yankees vs LA Dodgers

The first two games of the Yankees vs Dodgers World Series were played in New York.

While in other professional sports – including hockey and basketball – teams were granting women full access to the players, baseball did not.

Many of the important pre- and post-game interviews took place in the clubhouses. Melissa had worked with the Yankees before, earning their trust and securing a locker room pass to the team’s last two games in the ‘77 season.

She hoped to have similar access to the Dodgers players for the World Series, and as a courtesy approached them to arrange access.

Her World Series press pass said she had the right to work in the clubhouse.

Still, the Dodgers’ players took a vote.

“It wasn’t unanimous, but the majority voted to give me access, recognizing that being in the clubhouse was part of the job,” she said. “That’s where interviews were conducted.”

But when the Major League Baseball Commissioner heard about it, Melissa was told that under no circumstances could she enter the clubhouse.

She was banned.

Melissa was told by the Baseball Commissioner’s lieutenant that there were two reasons she couldn’t have access.

The first was that they hadn’t discussed the issue with the players’ wives.

Upon hearing this rationale, she responded:

“Give me an example of an issue Major League Baseball has discussed with the players’ wives.”

The second reason given was that ‘the children of the players would be ridiculed in their classrooms’ if Melissa was given access.

“That one seemed so ludicrous to me that I was actually left speechless,” she said.

She followed the orders and stayed out of the clubhouse – and said nothing to her bosses at Sports Illustrated.

“Women wouldn’t go to their bosses for help back then. You knew you were replaceable with a man.”

But word of her ban got out.

“When I got back to the office after Game 2, my editor called me into his office and asked what was happening at the Stadium,” she said. “I told him, but didn’t expect him to do a lot.”

But her editor did take action, and reached out to the baseball Commissioner.

By Game 6, a compromise was reached, which she agreed to abide by, but only under protest.

Melissa could not enter the clubhouse – but she would be assigned a male escort who would bring players out of the clubhouse to talk to her.

“I knew it wouldn’t work – and it didn’t. Even my escort recognized it didn’t work.”

Game 6: One for the History Books

Game 6 of the World Series was played on October 18, 1977 – one week after Melissa had been banned.

The Yankees were up in the Series, 3 games to 2.

This could be the night when history was made.

And it was.

Reggie Jackson, a man dubbed ‘Mr. October’ after he hit three home runs in three at bats, helped the Yankees win the game – and the World Series.

Melissa, along with the other reporters, headed toward the clubhouse at the end of the game to capture the celebration.

But instead of getting quotes from the players, Melissa found herself standing in a concrete hallway just outside the clubhouse – separated from the story.

She watched as TV cameras and men without credentials walked past her and entered the clubhouse. Across the country, men and women watched the jubilant celebration on live TV in the locker room – while she stood outside the door.

“I didn’t even have a TV monitor to see what was happening – even though people across the US were seeing what was happening on TV.”

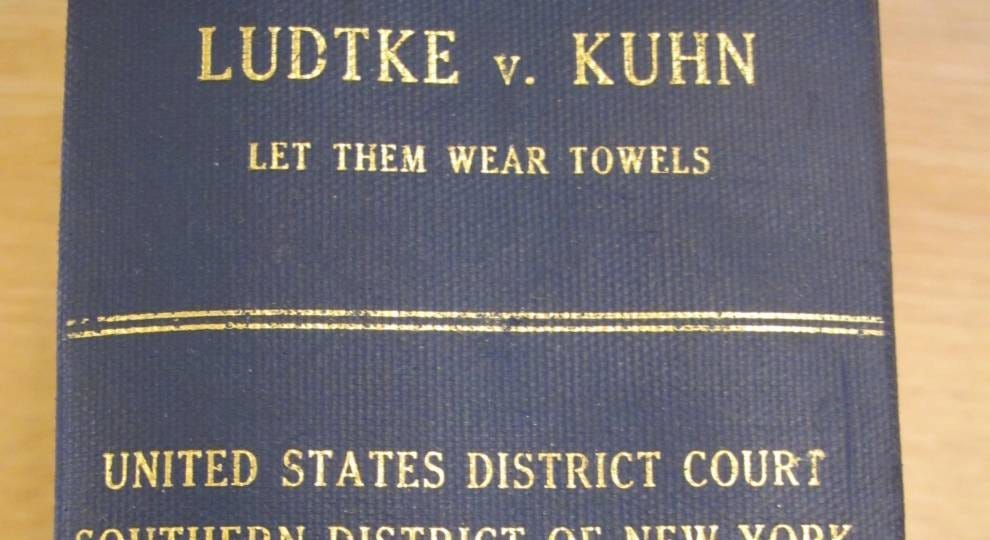

Her editor asked Melissa to write a letter to Commissioner Kuhn and explain what had happened to her that night. A few months later, she was named as the plaintiff on a lawsuit that Time Inc (owner of Sports Illustrated) filed against Major League Baseball.

“The case wasn’t about locker rooms,” Melissa said. “It was about equal rights.”

“I just wanted access to the players to do my job.”

And a judge agreed with her.

Ludtke vs. Kuhn was a victory for Time Inc, Sports Illustrated, and Melissa.

It was a victory for women everywhere – including the tens of thousands of female journalists who have followed in Melissa’s footsteps.

Being a game changer

What was that like, taking on Major League Baseball? Being the only woman in the room?

“It was hard,” Melissa told me. “People were saying awful things about me. I just wanted to do my job. I was the only woman, and was figuring it out myself.

“My instincts told me to get along, and make it work. But it was exhausting.”

So what does Melissa hope people take away from her case?

“This was an equal rights struggle,” she said.

“Young women don’t think there’s a lot left to do – but there’s still work to be done. We argued the legal barriers, but we still need to make attitudes align to the law.”

But she’s reassured by how far we’ve come.

“There are many women sports reporters and broadcasters today,” she noted.

“We have the Association of Women in Sports Media to support them. Women are reporting major league baseball – and minor league baseball. And every other sport. They are a pipeline to the future.

“There is still much to be done, but enormous progress has been made.”