Hello friends!

Do you still play board games? I say ‘still’ because I’m guessing many of you (whether you’re my age or not) played board games where you were a kid.

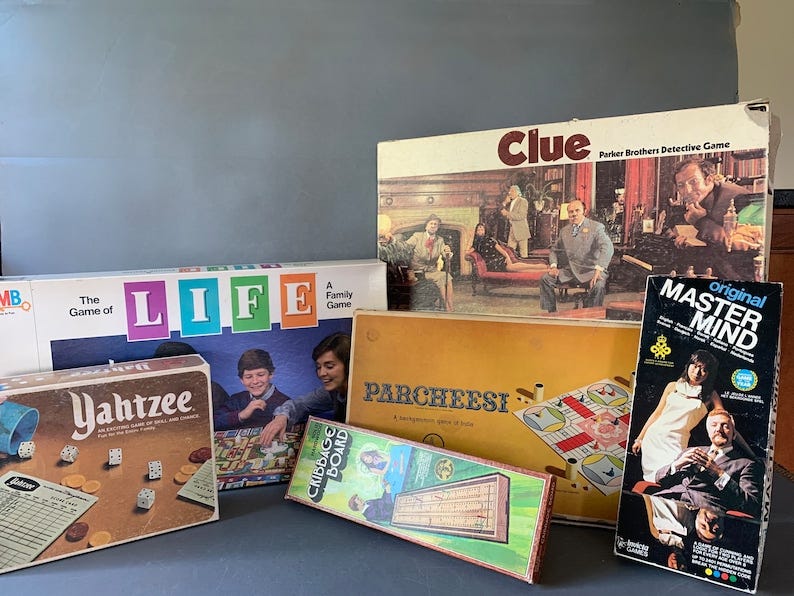

I remember playing Life, Clue, and of course, Monopoly.

Some of you may recall my curiosity deep dive into Monopoly from a 2022 issue of Curious Minds (if not, please check it out).

That’s when I learned that Monopoly was not the invention of a poor out-of-work man during the Great Depression, but actually a woman, Elizabeth Magie, who created the game to show the danger of monopolies.

Last month my daughter was given Monopoly for Christmas, and it got me thinking about another board game that has been popular for decades…

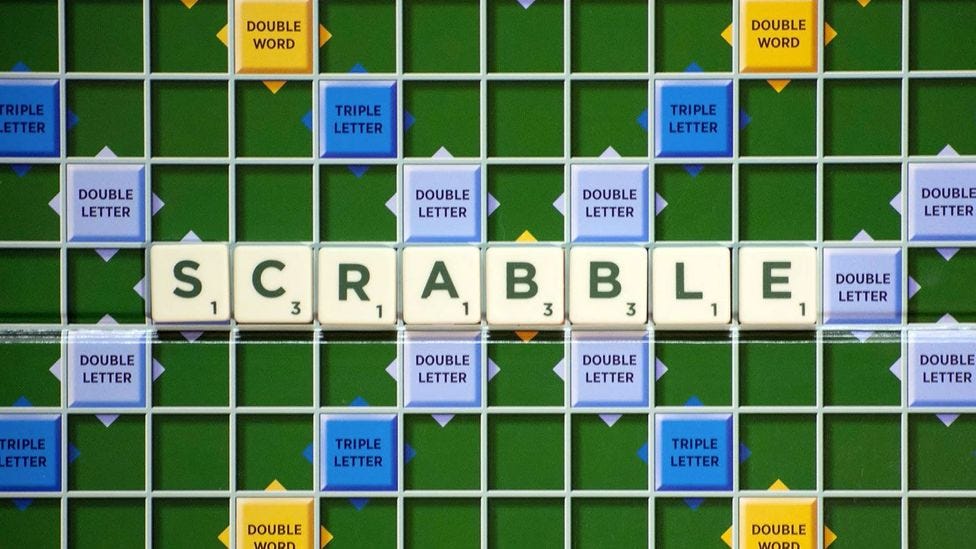

Scrabble.

But what’s the story behind Scrabble?

And does it have a happier origin story than Monopoly?

I was curious…

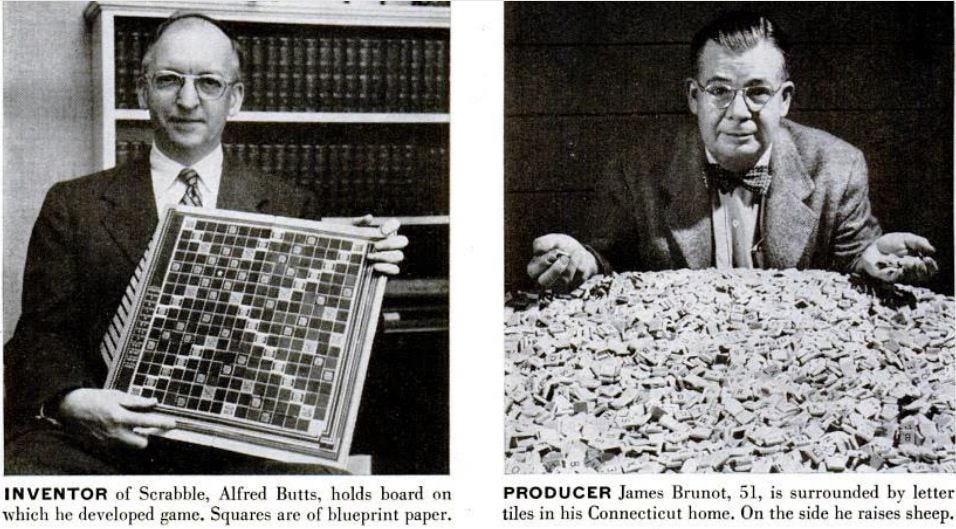

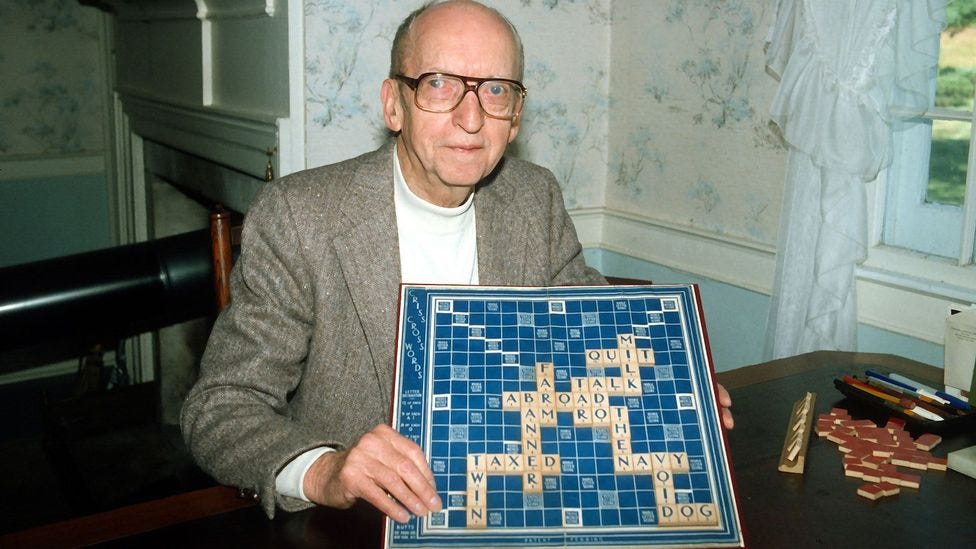

The story of Scrabble begins in 1931, when a man named Alfred Butts had a problem.

The shy architect from Queens, New York had lost his job.

He tried to make a living at painting, but that didn’t work.

He got a part-time job as a statistician, and inspired by Charles Darrow’s success with Monopoly, decided to create a game that he could sell.

He did his research, typing up a document he called Study of Games, where he identified three kinds of games: move games (like chess), number games (like Bingo) and word games.

Alfred noticed that there were many successful games in the first two categories, but saw an opportunity in the category of word games.

“It is curious that while two of the three bases of table games have yielded such interesting developments, the third has produced nothing better than Anagrams,” he wrote.

Alfred was fond of chess, crosswords, and jigsaw puzzles, which all influenced his new word game.

His game was also inspired by a short story he read as a child — Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold-Bug.

In the book, a character decodes a pirate’s coded treasure map by comparing symbols to letters.

Poe wrote:

“Now, in English, the letter which most frequently occurs is e.

Afterwards, the succession runs thus: a o i d h n r s t u y c f g l m w b k p q x z.”

Alfred thought about assigning values to letters for his game, and scoured newspapers including The New York Times, The New York Herald Tribune, and the Saturday Evening Post to determine the appropriate value he should assign each letter.

He sampled thousands of words to come up with the – presumably – statistically reliable breakdown of letters.

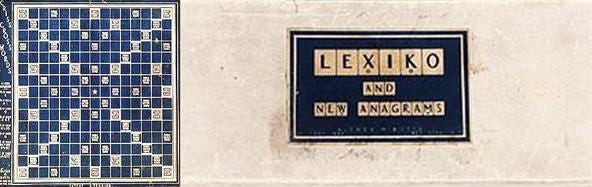

Then he called his game Lexiko.

Alfred made the games himself, hand-lettering the tiles and gluing them to balsa wood. His first iteration of the game did not include a board.

He sold Lexiko to friends for $1.50 each.

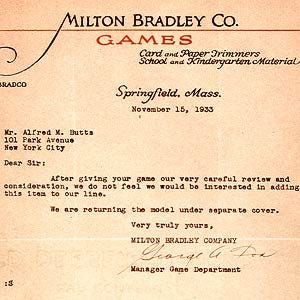

He tried to interest game manufacturers, including Selchow & Righter, Milton Bradley, and Parker Brothers.

But they all passed.

The Parker Brothers rejection letter dated October 17, 1934 read:

“Dear Mr Butts,

Our New Games Committee has carefully considered the game which you so kindly sent in to us for examination.

While the game no doubt contains considerable merit, we do not feel that it is adaptable to our line.”

But Alfred didn’t give up.

He decided to add a board to Lexiko so words could be created crossword style, and introduced blank tiles and premium-score squares.

Seven years after he started, he rebranded his game as Criss-Cross Words.

Alfred and his wife Nina would test out his tweaks, and they organized social events at a church hall in Queens where locals could test out new versions of his game.

But he still couldn’t sell the game.

His application for a patent was turned down.

By 1934, he’d sold just 84 handmade sets of his game – at a loss of $20.

Fortunately, the economy perked up, and Alfred was able to resume his old job at the architectural firm.

Alfred’s word game may have quietly disappeared at this point, if not for a man named James Brunot.

Brunot, a former social worker, had spent the second world war as director of the President’s War Relief Control Board, and was an aspiring entrepreneur.

He had owned Criss-Cross Words and saw its potential, though his letter to Alfred suggested otherwise.

“It seems apparent there is no marketable proprietary interest [in the game],” James wrote to Alfred.

But the two men struck a deal.

James would make and sell the game, and Alfred would receive a small royalty for each copy of the game sold.

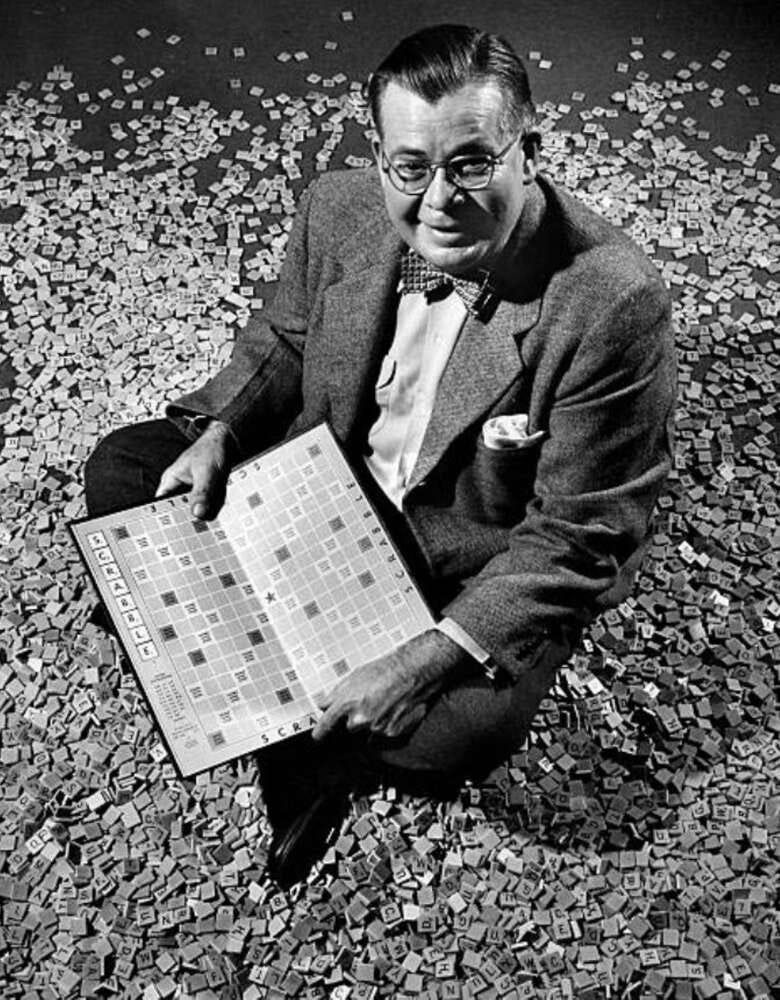

James Brunot took Alfred’s game and ran with it.

He came up with the color scheme (pastel pink, baby blue, indigo, and bright red), and the 50-point bonus for using all seven tiles to make a word.

He bought strips of scrap lumber, silk screened letters onto them, and hired woodworkers to saw them into tiles.

And either he (or his wife Helen) renamed the game Scrabble, which they received the copyright for in December 1948.

Working together, the Brunots assembled 2,251 copies of Scrabble in their living room during 1949.

And they lost $450.

But the Brunots persisted.

In 1951, they sold only 4,853 sets, but then everything changed in 1952.

That’s when the Brunots came home from a week’s vacation, and found orders for more than 2,000 games.

According to legend, Jack Straus, president of Macy’s department store, had discovered Scrabble while at a summer resort.

When he returned from vacation, he tried to buy a set from Macy’s – only to discover they didn’t stock it.

They soon did – and demand for the game soared.

The Brunots now needed more space for production, and first moved production to an abandoned schoolhouse in Newtown, Connecticut, and then to a converted woodworking shop.

In 1952, they had 35 workers making 6,000 games each week – and it was still not enough to keep up with orders.

Being unable to keep up with the growing demand, James Brunot decided to license the game to Selchow & Righter, but kept the rights to make a deluxe version himself.

What was different about the deluxe version? The pieces were made with plastic.

In 1953, Selchow & Righter sold 800,000 Scrabble games, but demand still outweighed supply.

“Buying a Scrabble set in New York today is akin to nabbing a prime rib roast at ceiling price during World War Two,” wrote the World-Telegram.

Christmas shoppers had to either put their names on a waiting list, or linger by a store counter hoping for a new shipment to arrive.

In 1954, 4 million copies of Scrabble were sold.

In 1972, Selchow & Righter, having turned down the game years earlier, bought trademark ownership from Brunot.

Alfred Butts agreed to give up his future royalties in return for a lump sum.

He got $265,000 in the deal.

James Brunot walked away with $1.3 million, but Alfred Butts apparently didn’t mind.

According to his great nephew Robert Butts:

“Alfred had no regrets about all that.

“He was sort of pleasantly surprised by the whole thing. It wasn't his nature to have regrets.

He was just thankful for all his good fortune, I think.”

Alfred Butts may not have become a multi-millionaire from Scrabble, but he made enough money to buy a farmhouse outside Poughkeepsie, New York (that had once belonged to his ancestors).

When asked about the money he received from his game, he responded:

“One-third went to taxes, I gave one-third away, and the other third enabled me to have an enjoyable life.”

Alfred Butts die in 1993, at age 93.

Scrabble was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 2004. The game has been produced in 30 languages, and is available in 121 countries.

One out of every three American households has a Scrabble game – and more than half of British households have Scrabble.

More than 150 million copies of Scrabble have been sold, and Alfred’s creation has entertained (and continues to entertain) millions of people around the world.

FUN FACT:

Benjamin Woo discovered a way to earn 1782 points – the highest possible score — for OXYPHENBUTAZONE. He played it across the top of the board, hitting three Triple Word Score squares while making seven crosswords downward.

BONUS FUN FACT

John Chew, co-president of the North American SCRABBLE Players Association, got death threats when he removed the two-letter word ‘da’ from the Scrabble Dictionary.

AND LAST ONE…

Alfred Butts may have invented Scrabble, but he was not a good speller.

Recent Work and Writing

I’m still suffering from jet-lag (ARG!!!) but had enough energy to write another story this week!

Loose Lips Lose Leo — Poor communication can cost you your career, your reputation, and …Leonardo DiCaprio?

And don’t forget to check out the lessons that can be gleaned from the best and worst communication moments of 2022:

Santa’s Naughty List — See whose communication skills earned them a lump of coal this year.

Santa’s Nice List — These people earned a spot on Santa’s Nice List with their communication skills.

The ONE thing that matters most when you’re giving a speech — Trust me, folks. If you’re giving a speech or a presentation, this is where you need to focus.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff showed us how poor communication can hurt your reputation last week, and 1980s hunk Lorenzo Lamas showed us how loose lips can lose your daughter her chance to be Leonardo DiCaprio’s girlfriend.

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

![Edgar Allen Poe - The Gold Bug - Thomas Crowell, n.d. [1910], Later Edition. Edgar Allen Poe - The Gold Bug - Thomas Crowell, n.d. [1910], Later Edition.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!b4Cb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6916ac5b-c0b8-424d-ba80-ced8e4d27a7c_768x1152.jpeg)

Board game rejection letters...who knew?

Butts’ humility is admirable.

Lifelong LIFE game fan, here who still misses the OG “millionaire acres” version