Did you ever have a school project that you were obsessed with?

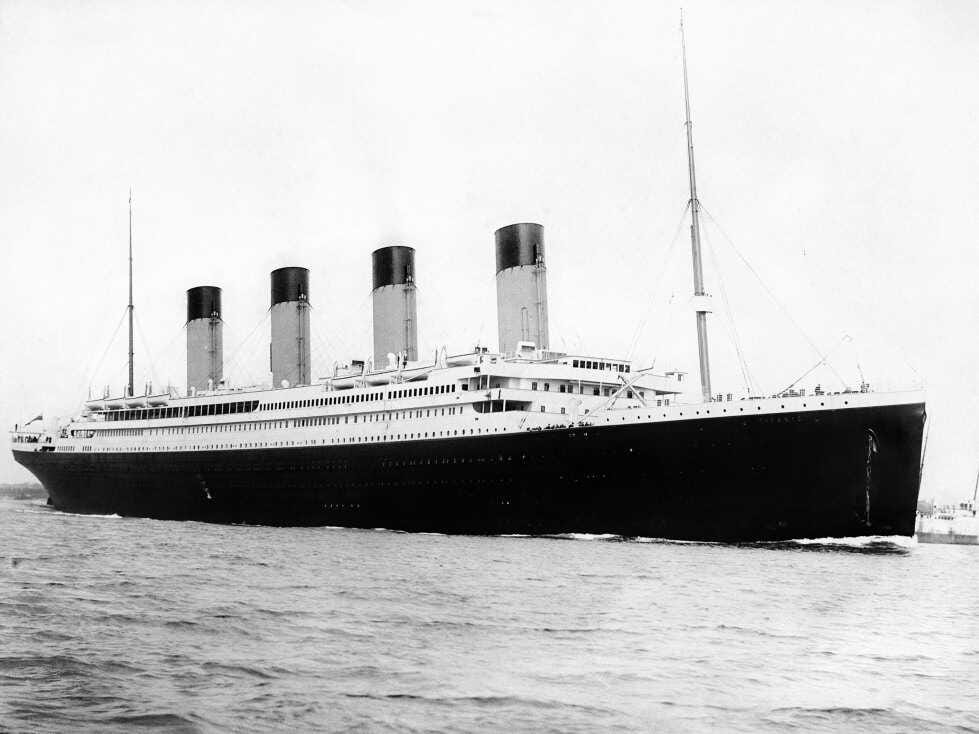

One of mine was Titanic.

I must have been about 9 or 10 years old when I first started learning about the Titanic — back when research required going to the public library.

I can remember going to the library with my mom and reading articles about the Titanic on both microfilm and *microfiche.*

I don’t know why I found the story about the Titanic so interesting, but I was fascinated.

And when the film Titanic came out (years later), I was the nerd sharing fun facts after the credits rolled.

But there is one story that didn’t make it into James Cameron’s film that I was still wondering about.

In one of the deleted scenes, we see a wireless operator on the Titanic ignore another ship’s warning about the ice — rudely responding on the wire for them to ‘shut up.’

But did this really happen?

If you do a google search, you can find several sources that repeat this story, and criticize Titanic’s wireless operator, Jack Phillips, and his ‘rudeness’ on the wire that night.

But who was Jack Phillips, and what really happened?

I was curious…

I began researching, and my curiosity had me fall down a rabbit hole of Titanic articles, old maritime books, and detailed testimony from inquiries in the US and Britain from 1912.

And a different story emerged than the one I was expecting…

It starts with George ‘Jack’ Phillips, who was born in Farncombe, UK in 1887, and learned telegraphy at the nearby Godalming Post Office.

He then went to work for the Marconi Company, graduating as a wireless operator in August 1906.

He was assigned to the White Star Line and worked aboard more than a half-dozen ships before becoming Chief Telegraphist on their new luxury ship, RMS Titanic, in 1912.

Titanic was equipped with the most up-to-date wireless of the time.

It was guaranteed to reach 350 miles, and could exceed that distance at night.

The Marconi technology was something of a novelty at that time, and the job of a telegraphist was to communicate with other ships and relay passenger messages.

Most passenger ships had one telegraphist onboard, but Titanic had two.

Jack Phillips was joined by a junior operator, 22-year-old Harold Bride, who had been with the Marconi Company since July 1911.

The two men kept busy sending and receiving messages for the hundreds of well-to-do passengers, as well as with routine ship traffic, news and weather bulletins.

But as Titanic sailed across the Atlantic on April 13, 1912, Phillips and Bride had a problem.

Their wireless machine wasn’t working.

The Marconi manual (and company policy) stated that telegraphists were not to attempt repairs at sea.

Rather, they were to wait until reaching port, where a Marconi engineer could be called to repair the machine.

But the two young men ignored those rules.

Instead, they spent six hours trying to fix the machine, eventually managing to resolve the problem by binding the leads of the transformer with rubber tape.

With the machine now back in perfect working order, Phillips and Bride began working on the backlog of messages they had to send.

The wireless was fully functioning the next day, Sunday April 14, and the two men carried on sending and receiving messages that day, including ones of ice warnings.

Cyril Evans, the wireless operator aboard the ship Californian, testified that he had sent an ice report to the ship Antillian Sunday afternoon.

Hearing the correspondence, the Titanic called up the Californian, and they exchanged signals.

The Californian shared the ice report, and the Titanic replied,

“It’s all right, Old Man. I heard you send to the Antillian.”

These warnings were shared with Titanic’s captain, Edward Smith.

Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, who was onboard Titanic, testified to the US Senate Inquiry that Captain Smith had shared the ice warnings with him as well.

But as Sunday evening wore on, Jack Phillips was exhausted.

He had sacrificed his rest time the day before to fix Titanic’s wireless machine.

And he had a large number of passenger messages to send.

Brice was resting late that evening while Phillips was sending messages to the shore station of Cape Race in Newfoundland.

The signal from Cape Race was faint, and required even more concentration and effort from Phillips to interpret their messages.

It was then that a loud signal came shouting through his headset.

It was the Californian.

Their Captain had decided to stop because of the ice.

“Better advise him [Titanic] we are surrounded by ice and stopped,” the Captain reportedly told Evans.

Evans returned to his cabin and called up Titanic.

“Say, Old Man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice,” he wrote to Titanic.

“Shut up, shut up I am busy; I am working Cape Race,” Titanic replied.

This is the story that has been shared for a century – and often where it stops.

But there is more to the story.

To understand what really happened, you have to understand who these young telegraphists (also referred to as ‘Marconi Men’) were — and what the job of a telegraphist involved.

Think of them as the ‘tech bros’ of the early 1900s.

A fraternity of young men who were inclined to use shorthand language like OM (for Old Man) and the incredibly saucy GTH (Get to Hell - an expression considered so rude that a Titanic crew member wrote it on paper rather than say it aloud during the US Senate Inquiry).

Many of the Marconi Men trained together, and were friends (or at least colleagues) who would communicate while at sea.

And their job wasn’t easy.

The channels were open to everyone at the same time, so Titanic’s operators were transmitting over the same frequency as other ships.

And – here’s where it gets really interesting…

Evans was not annoyed by the message Phillips sent him.

As he would later testify in a British Inquiry on May 15, 1912, he understood what Phillips said – and what he meant.

“Well, Sir, he was working to Cape Race at the time,” Evans testified.

“Cape Race was sending messages to him, and when I started to send, he could not hear what Cape Race was sending.”

Evans understood that he was interfering with Phillips doing his work, and the message to ‘shut up’ (or ‘keep out’) was not considered curt or rude at all.

“In ordinary Marconi practice, is that a common thing to be asked?” the British Solicitor-General asked Evans.

“Yes,” he replied.

“And you do not take it as an insult or anything like that,” Evans replied.

Evans understood – and testified – that a Marconi operator could only clearly hear one thing at a time, and that his message had jammed Phillips, interfering with the messages Phillips was receiving from Cape Race.

So it’s impossible to know if Phillips even heard the message Evans sent.

It’s also clear that Phillips wasn’t being rude — or seen to be rude by Evans.

And regardless, Titanic had received – and already relayed – the ice warnings to their captain earlier in the day.

Phillips could easily have interpreted Evans message as idle chit-chat, as Evans did not use the prefix ‘MSG’ to indicate it was a message for the bridge.

Evans testified that after receiving the message from Phillips, he kept the phones on for another 10 minutes or so, and heard Phillips continuing to send messages to Cape Race.

After working a 16-hour shift, at 11:35 pm, Evans ‘put the phones down and turned in.’

The Titanic hit the iceberg at 11:40 pm.

Thirty-five minutes after Titanic struck the ice, Captain Smith advised Phillips and Bride to send the distress call.

Phillips, the senior operator, was on the phones.

For nearly two hours, he sent messages of CQD and SOS (the new distress call) across the wire.

The Carpathia, nearly 60 miles away, immediately changed course and headed toward the danger to rescue Titanic.

Other ships, including the Baltic and Olympic also came to help – though they were much farther away.

Phillips continued sending messages in the hopes of reaching a ship that might be closer.

Even after Captain Smith dismissed him and Bride at 2 am, Jack Phillips continued sending messages for 15 minutes more, even as the power was dying and water was filling the decks.

Phillips was not a villain in the Titanic story.

He was a hero.

His skills and sacrifice saved more than 700 people aboard Titanic.

And had he not ignored the rules and fixed the Marconi on April 13, no one would have been saved.

Phillips did not survive the Titanic disaster, but junior operator Harold Bride did.

Bride would recount to the New York Times on 19 April 1912:

“He (Phillips) was a brave man.

“I learned to love him that night and I suddenly felt for him a great reverence to see him standing there sticking to his work while everybody else was raging about.”

“I will never live to forget the work of Phillips for the last awful fifteen minutes.”

One more thing…

You can see a log of the messages that RMS Titanic (and other ships) sent on the wireless in the early morning of April 15, 1912 (as Titanic was sinking).

More thoughts on curiosity!

What Do You Know to Be True?

Roger Kastner asked me this question for his podcast of the same name.

Curious what I know to be true?

Check out our conversation: “Following Your Curiosity to Find Truth and Joy with Beth Collier” on YouTube, Apple Podcasts, or Spotify.

And speaking of curiosity…

I had the opportunity to chat all things communication and curiosity recently with Katie Macaulay on The Internal Comms Podcast.

Have a listen and find out how my high school’s motto inspired me — and what I learned from all those high-flying execs I encountered when I was photocopying (and faxing) their documents in Hollywood.

I also share why I believe “Imposter Syndrome” is a garbage concept, and why duct tape inspires me (yes, really).

You can listen to our conversation on Spotify or Apple podcasts.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, stay curious!

-Beth

This was fascinating! And that picture of the actual iceberg!