Still watching the Olympics?

I’ve been making the most of my Discovery+ subscription, celebrating the victories of Team USA and Team GB and so many others.

It’s fair to say the Olympics have been on my mind…

Last week, I shared a story about the evolution of the high jump – and if you read all the way to my “One More Thing” at the end, you would have seen this video from 2021 when Gianmarco Tamberi of Italy and Qatar’s Mutaz Barshim opted to share the gold medal for the high jump at the Tokyo Olympics.

In case you missed it, here’s a refresher:

Opting to share a gold medal.

Isn’t that nice?

But it got me thinking…how often do athletes choose to share a medal?

And was there an example when the Olympics did not allow this?

I was curious…

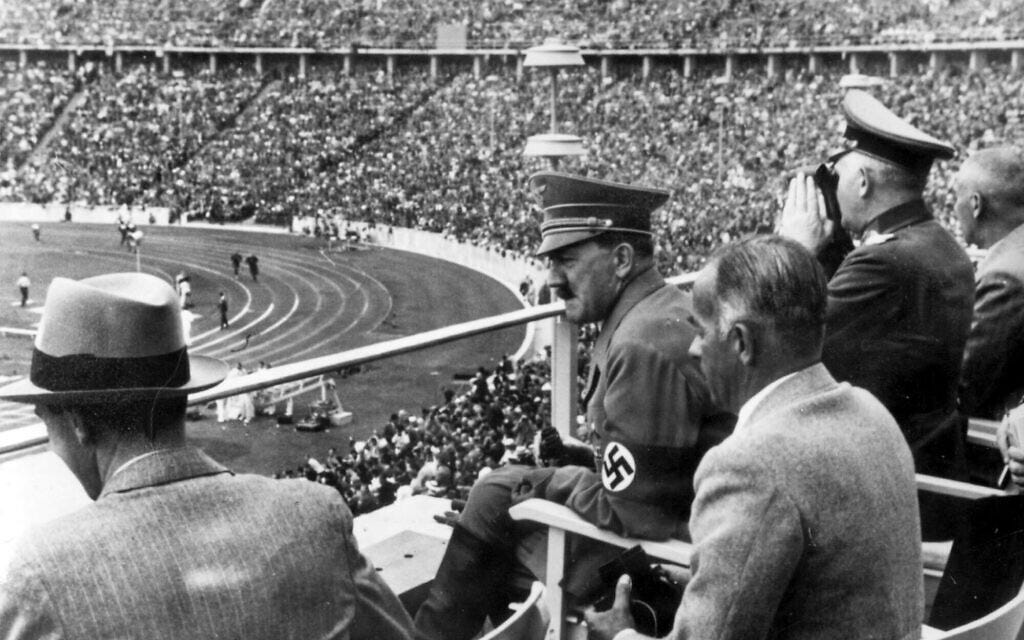

My curiosity led me to the 1936 Olympics.

You might know them as the “Nazi Olympics”, as they were held in Berlin when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party had risen to power.

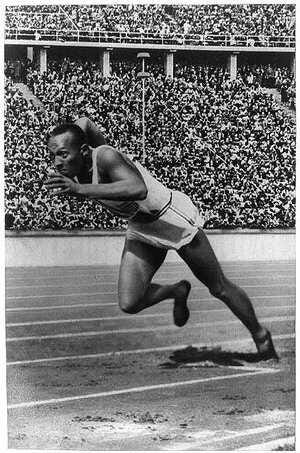

Or maybe you know them because of the success of American runner Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals at the games.

But as Hitler was excluding Jews from competing and showing us the worst of humanity, two other athletes showed us the best of it.

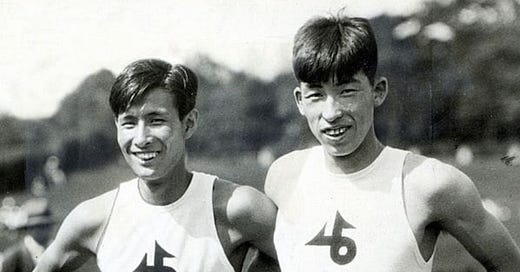

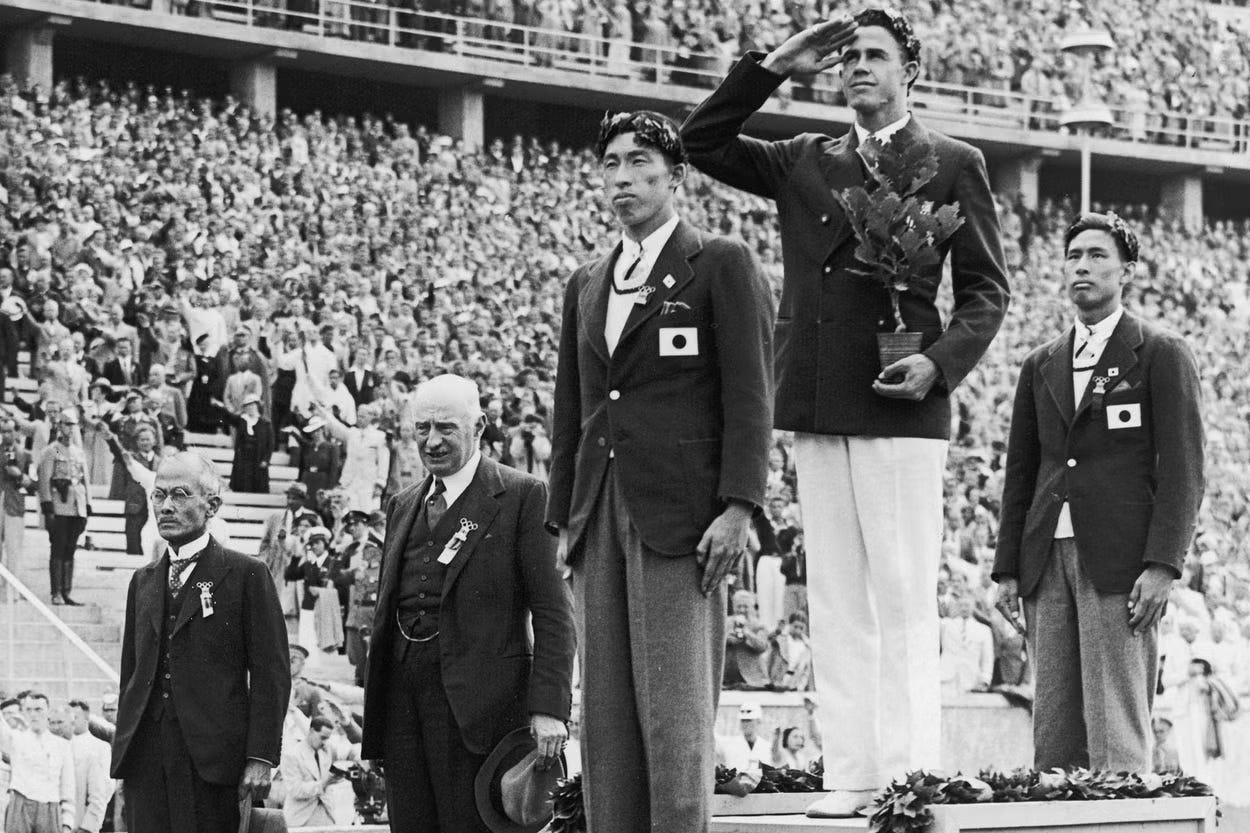

Meet Japan’s Shuhei Nishida and Sueo Oe.

Both men1 were among the best pole vaulters competing in the 1936 Olympics.

After they both cleared an impressive 4.15m2, they advanced to the final stage of the men’s pole vault competition.

An audience of 25,000 watched as the men battled for the gold medal.

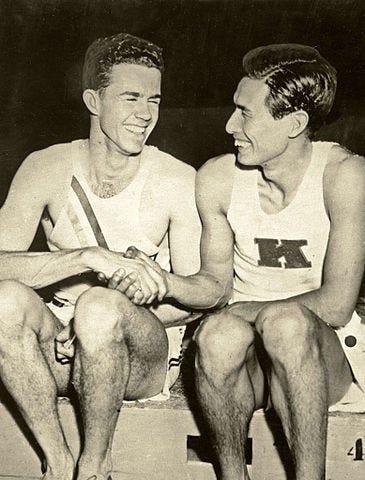

Nishida, Oe, and Americans Bill Sefton and Earle Meadows all cleared 4.25m.

But Meadows was the only finalist who cleared 4.35m, securing the gold medal.

But now the race was on for silver.

At this stage of the jump-off, Sefton failed to clear the bar on the first try.

But both Nishida and Oe were successful – meaning they would join Meadows on the winner’s podium.

And here’s where it gets really interesting.

Nishida and Oe – who were friends – refused to compete any further.

Instead, they asked to share the silver medal.

But the Olympic officials refused.

The Japanese team decided that Nishida would be awarded the silver medal and Oe would receive the bronze.

As for the reason, several theories exist.

Perhaps it was because Nishida had cleared 4.25 on his first attempt, something it took Oe two attempts to achieve.

Or maybe it was because Nishida was four years older than Oe, and it was a sign of reverence, or an acknowledgement that Oe had a better chance of winning at another Olympics.

But regardless of the rationale, Nishida and Oe were clearly not satisfied with the decision.

And when they returned to Japan, they took matters into their own hands.

The two friends took their medals to a jeweler, and asked that they be cut in half and then fused into two new medals: each half-silver and half-bronze.

These medals would come to be known as the “Medals of Friendship.”

Oe and Nishida were hoping for a rematch in 1940, but the Olympic games were canceled due to the outbreak of World War II.

Oe died in the war in 1941.

Nishida never returned to compete at the Olympic games, but he remained active in sports throughout his life. He continued to compete in the pole vault after the war, and won a bronze medal at the 1951 Asian Games when he was 41 years old.

Nishida passed away in 1997 at age 87.

Oe’s medal is held privately, but Nishida’s was donated to his alma mater, Waseda University in Japan.

And their story of camaraderie and friendship continues to inspire.

One more thing…

In case you’re curious, here’s footage of the pole vault final from the 1936 Olympics:

What Else Is On My Mind?

In Defense of the “Childless Cat Ladies” — Why do some people think it’s appropriate to opine on a woman’s reproductive status? I have some thoughts…

You Are Not an Imposter

Earlier this year, my curiosity took me to dig deep into the background of “Imposter Syndrome” — and I’ve developed a new workshop to help people understand what this concept is really about — and how to overcome the all-too-common “Imposter” feelings.

I’ve shared it with a few clients already, but want to spread the message far and wide. If you know of an organization that could use an “knowledgeable, thought-provoking, energetic speaker”, get in touch!

I’ve also pitched to run this workshop at the 2025 SXSW Conference, and I am asking for your help!

Part of the selection process for SXSW includes a public vote, and I’d appreciate your support in voting for my workshop “You Are Not an Imposter: Banish Your Imposter Syndrome” for the 2025 Conference.

You can see the proposal and vote here.

Thank you in advance for your support!

How can I help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap massive rewards – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

Apologies for any mispronunciation. I do look up how to pronounce names and words in languages I don’t speak, but may not always nail it like a native speaker!

4.15m was impressive for the time. Sweden’s Armand Duplantis won the gold medal in Paris with 6.10m (and set an Olympic record). He also holds the world record of 6.24m, which he set in April 2024. But things were different in 1936.