Hello!

Recently, I learned of a campaign called “Correct The Internet.”

It is raising awareness of the way google (and other search engines) give priority to the accomplishments of male athletes over female athletes — and what we can do to correct it.

When I asked google which USA soccer player has scored the most goals, the first page of search results said Landon Donovan and Clint Dempsey were tied with 57 goals.

But when I added the word ‘female’ to that search, I discovered that Abby Wambach has scored more than three times the goals Landon or Clint have!

I then asked google “Which tennis player has spent the longest time ranked number 1?” and saw this guy had been ranked No. 1 for 237 weeks.

But, when I added the word ‘female’ to my search, I discovered that Steffi Graf held the number 1 spot for 377 (!) weeks.

Why are these women’s accomplishments being erased?

I decided to write about this, and that’s when one person asked me,

“Have you heard of the Matilda Effect?”

I hadn’t, but of course, I was curious…

The Matilda Effect was coined by a science historian named Margaret Rossiter in 1993.

Rossiter was born in 1944, and developed an interest in the history of science as a high school student.

“I always found the ‘humanizing of science’ more interesting than the actual science,” she wrote in her essay Writing Women into Science.

Rossiter discovered ‘History of Science’ as a major at Radcliffe, and after graduating in 1966, went to work for the Smithsonian.

She then went on to earn a master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, followed by a PhD at Yale in 1971.

Margaret was one of few women studying the history of science at Yale, and made a point to join her department’s professors and students for social gatherings every Friday afternoon.

At one of these informal get-togethers, surrounded by men who shared her interests in science and history, Rossiter casually asked if there had ever been women scientists.

The group was unanimous – no.

Never.

“It was delivered quite authoritatively,” said Rossiter.

Although someone suggested Marie Curie, the others dismissed it, saying Marie’s husband Pierre really deserved the credit for their work.

Rossiter did not argue, and realized “this was not an acceptable subject.”

But the group’s dismissal of women in science made her curious – and that curiosity led her to her life’s work, uncovering the history of women in American science.

In her research, Margaret Rossiter began collecting stories of forgotten women who had been astronomers, physicists, chemists, entomologists, and botanists.

“I felt like a modern Alice who had fallen down a rabbit hole into a wonderland of the history of science,” she said.

She uncovered biographies of hundreds of women scientists, and found there were many untold stories – enough to fill a book – which she published in 1982: Women Scientists in America, Struggles and Strategies to 1940.

“It is important to note early that women’s historically subordinate ‘place,’ in science (and thus their invisibility to even experienced historians of science) was not a coincidence and was not due to any lack of merit on their part,” Rossiter wrote.

“It was due to the camouflage intentionally placed over their presence in science.”

Rossiter would go on to profile even more women scientists in two more volumes: Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action, 1940-1972, and Women Scientists in America: Forging a New World Since 1972.

“Her work showed that there were women in science, and that we could increase those numbers, because women are quite capable of it,” said Londa Schiebinger, a historian of science at Stanford University.

Over decades of research, Rossiter proved that the professors and students she met during her studies at Yale were wrong: Women were capable of great scientific work – and too often their contributions were ignored, stolen, or lost.

Her work also showed the barriers women scientists faced – and that administrators needed to reform academic institutions so that women scientists could thrive.

She had the research to prove her point, but how could she make her point stick?

The answer came to her in the early 1990s.

She read an obscure book about overlooked women intellectuals, and shortly after that, attended a conference where researchers presented papers about women scientists whose work had been incorrectly credited to men.

“It was a phenomenon,” she said.

She wanted a term to apply to the historic bias against recognizing the achievements of female scientists, and a situation when a man received credit for groundbreaking work done by a woman.

“This happens a lot. It needed a name, because giving it a name makes it stick with people.”

She decided on The Matilda Effect, named after one of the overlooked women intellectuals she had read about: Matilda Joslyn Gage.

Rossiter introduced the term in a 1993 paper called “The Matthew Matilda Effect in Science” for the journal Social Studies of Science.

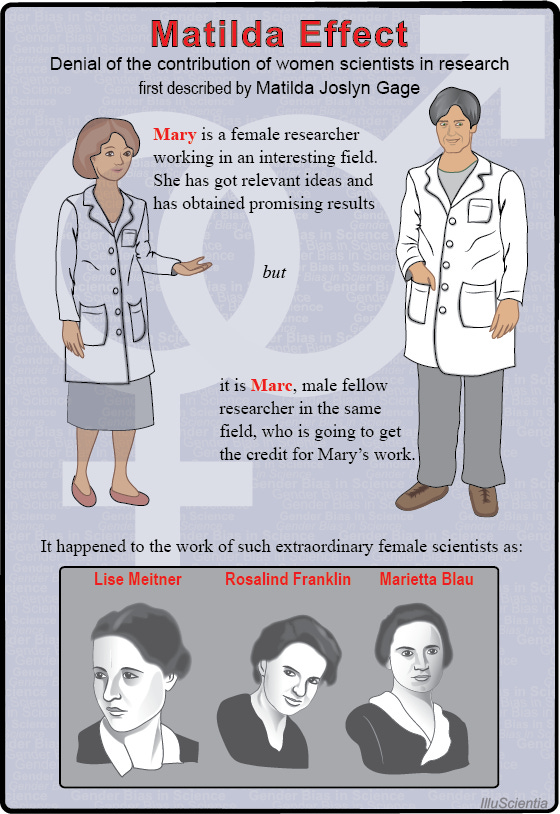

The Matilda Effect:

The historical and systemic bias against recognizing the contributions of women scientists and instead attributing their work to their male colleagues.

She detailed how women scientists had been ignored, denied credit, or otherwise dropped from sight, similar to other fields like medicine, art history, and literary criticism.

She noted that sociologists had already recognized how eminent scientists would often receive credit for the work of scientists with less recognition (“The Matthew Effect”, a term coined in 1968), and that calling attention to this “age-old tendency” could lead to a better, more comprehensive history of science.

She shared examples like Rosalind Franklin and Lise Meitner, and highlighted women whose contributions to science had been overlooked, diminished – or simply erased.

And she wrote how she had been inspired to coin this phenomenon after Matilda Joslyn Gage, a nineteenth century suffragist who noticed a pattern of women’s achievements being diminished, deplored it, and whose own contributions were largely erased from history.

Since Rossiter coined the term in 1993, “The Matilda Effect” has been cited in hundreds of studies, and helped raise awareness of both the contributions of women scientists, and the bias that can overlook their achievements.

Rossiter’s research and writing has given credit to the women scientists who came before her, and has also provided a framework for other scholars to build on.

Professor Rossiter taught courses on agriculture, women in science, and the history of science at Cornell University until her retirement in 2017.

Over her career, Rossiter received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a MacArthur Fellowship, and multiple grants from the National Science Foundation.

She also received the History of Women in Science Prize and the Pfizer Prize for “Women Scientists in America.”

And in 2022, Rossiter received the George Sarton Medal, the most prestigious award given by the History of Science Society, awarded to a historian of science for a lifetime of scholarly achievement.

Jessica Ratcliff, assistant professor of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell, applauded Professor Rossiter for highlighting what women in science have achieved, and illustrating the structural inequalities that have excluded them.

“Archive by archive, case by case, individual by individual, year by year, Professor Rossiter’s painstaking research has written women back into the history of science in America,” Ratcliff said.

Rossiter’s research has helped ensure that history does not leave all the “Matildas” out – and, as she wrote in her 1993 essay, “calls attention to still more of them.”

BONUS: The History of Science Society has awarded a Margaret Rossiter History of Women in Science Prize each year since 1987, recognizing an outstanding book or article on the history of women in science.

Margaret herself received the award in 1997.

One more thing…

In 2021, the non-profit AMIT, with the support of the European Parliament, created an awareness campaign to promote the scientific vocation to teenagers and girls.

They called it “No More Matildas.”

Here’s a video from the campaign:

Recent Work and Writing

One Communication Skill to Build in 2023 — It’s an underrated skill, but also a valuable one.

Work with Women? — Here’s something you should know.

Go Hug Yourself — We can do more to reach gender equity than this.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, stay curious!

-Beth

Thank you. As a woman scientist, I really appreciate this article.

Great article. I wonder how this naps out onto social science, too.