Someone asked me recently if I was worried I’d run out of ideas for Curious Minds.

“As long as I’m reading, listening, and thinking, I’ll be fine!” I replied.

And my inspiration for this week’s story came after I read that superstar Barbra Streisand was releasing a new book, My Name is Barbra.

As a fan of pop culture and music, I obviously know who Barbra Streisand is, but I wasn’t raised on the musicals and films she starred in from the 1960s-1980s.

But seeing her name in the news made me think of a term I’ve heard before —

The Streisand Effect.

But what exactly is it — and how did it come to be?

I was curious…

We begin our story in 2002, when a married couple named Ken and Gabrielle Adelman began an ambitious project.

The Adelmans, retired dot-com millionaires, wanted to capture and document images of the California coast to track erosion.

They self-funded the project, using their personal helicopter to fly around the California coast.

Gabrielle piloted the helicopter, while Ken leant out the side, snapping images roughly every three seconds.

They compiled thousands of aerial images as part of their California Coastal Records Project, and made them available on their website, www.californiacoastline.org

The Adelmans did not profit from the project. They were environmentalists who wanted to advance the cause of coastal protection.

“Our goal is to create a complete record of the California coastline,” they said.

Their website and images were used by numerous federal, state, and local agencies and scientists, free of charge — long before google images were ubiquitous.

But then on May 20, 2003, the Adelmans found out they were being sued – over one image they had published on their website.

At that point they had more than 12,000 images on their website – but Image 3850 had landed them in hot water.

The owner of the house in Image 3850 was angry that her property was being shared online, and she was suing the Adelmans for $50 million.

And the owner of the property was Barbra Streisand.

In the lawsuit, Streisand alleged that by sharing Image 3850 online, the Adelmans invaded her privacy, violated the “anti paparazzi” statute, sought to profit from her name, and threatened her security.

The Adelmans argued that their website included just one aerial shot that contained Streisand’s blufftop estate.

And her estate was actually a small part of Image 3850.

They had not included her address, driving directions to her home, or any interior shots of the home on their site.

In fact, they hadn’t even included Streisand’s name.

They also argued that the address of Streisand’s Malibu residence was easy to obtain online, and that images of the interiors had also been featured publicly.

“Mr. Adelman is not a paparazzo,” argued his lawyer Richard Kendall.

“He’s not doing this for profit, or stalking anyone. He is engaged in a public-interest effort to document the entire coast to preserve it from degradation.

“He’s not about to carve out exceptions for celebrities who don’t want to be identified as owning coastal land.”

But Streisand and her lawyers argued that her privacy had been violated.

“There is no telling how many people have downloaded the photograph of Plaintiff’s property and residence,” Streisand’s lawsuit alleged.

Except that there was.

When the Adelmans looked at their website’s activity before Streisand filed her lawsuit, they discovered that between February 14, 2003 and May 30, 2003, there were 14,418 downloads from the California Coastal Record Project website.

And Image 3850 – one of more than 12,000 available online – had been downloaded a total of six times.

Two of these were by Streisand’s lawyers.

The rest appeared to be by Streisand herself and some neighbors.

But – Streisand’s lawyers argued – the Adelmans were also selling the image, so anyone could purchase the image of Ms. Streisand’s property.

That was true.

Anyone could purchase the image.

But prior to the lawsuit, a whopping three reprints of Image 3850 had been ordered.

One purchase was from Streisand’s neighbors – with whom she was disputing her planned construction.

The other two reprints were ordered by Streisand.

So, no one really cared about the image of Streisand’s house – until she sued.

That’s when the lawsuit became public and the story hit the news.

Suddenly the public was very interested in the image that Streisand didn’t want people to see.

Image 3850 then became very popular, receiving nearly half a million views.

And on December 31, 2003, Streisand’s lawsuit was dismissed, and she was forced to pay the Adelmans’ legal bill and court costs to the tune of $177,107.54.

Then something similar happened in 2005.

A website that posted pictures of urinals (yes, really) found itself in a similar legal drama when the Marco Beach Ocean Resort objected to one of the resort’s urinals appearing on the website urinal.net.

This wasn’t the first time someone had taken legal action against the urinals website (yes, really!), as the Toronto Airport Authority had objected to their name appearing on the website in 2004.

The team behind urinal.net responded by posting the pictures from “the airborne vessel take-off and landing facility located near Canada’s largest city,” noting that it was “located on the outskirts of said city and is named after a person whose name starts with a ‘P’ and ends with an ‘earson.’”

“The three-letter code for this facility includes the letters Y, Y and Z, necessarily in that order.”

But the scandal of urinal images at the Toronto Airport and Marco Beach Ocean Resort suffered the same effect as the image of Streisand’s home.

Something that few would ordinarily care about suddenly became very interesting to the public.

And Mike Masnick, founder of the technology news website Techdirt, wrote:

“How long is it going to take before lawyers realize that the simple act of trying to repress something they don’t like online is likely to make it so that something that most people never, ever see (like a photo of a urinal in some random beach resort) is now seen by many more people?

“Let’s call it the Streisand Effect.”

It took a few years for the term to take off, but now Merriam-Webster defines The Streisand Effect as “a phenomenon whereby the attempt to suppress something only brings more attention or notoriety to it.”

And Streisand isn’t the only star it’s happened to.

Beyoncé also experienced the Streisand Effect after “unflattering” photos of her Super Bowl performance appeared online in 2013.

Her publicist wrote to Buzzfeed asking that the photos be taken down, identifying which images were “the worst ones.”

Buzzfeed responded by sharing the publicist’s email – and the photos – in an article, “The Unflattering Photos Beyonce’s Publicist Doesn’t Want You to See.”

“Unflattering Beyoncé” became one of the biggest memes of 2013, as the images of Queen B were photoshopped into other scenarios.

And there are plenty of examples of the Streisand Effect in action, from Uber and Ralph Lauren to a nine-year-old girl’s website about school lunches.

And some even seek out opportunities to capitalize on the Streisand Effect.

PETA has been known to submit provocative ads for the Super Bowl, knowing that they can get more publicity (for free) when the ads are rejected.

So, take this note from Streisand:

When you try to hide something on the web, everyone sees it.

Also, whatever you do, please do not visit or share this website with anyone!

One more thing…

There’s another (lesser known) Streisand Effect, too.

Director of horticulture Marco Polo Stufano was known for his “imaginative design concepts and startling plant combinations.”

In November 1992, The Vancouver Sun reported that Stufano put orange dahlias and pink asters together to create what he called ‘The Barbra Streisand effect’ – defined as “a jarring combination of plants that initially sets your teeth on edge but that you learn to appreciate for its strength of character, its gutsiness.”

But Stufano’s Streisand Effect didn’t catch on.

And here’s what pink asters and orange dahlias look like together, in case you’re curious…

Idea for the Day

I got inspired to make this video after a trip to my local coffee shop earlier this week.

No make-up. No script.

Just a message that I believe it important (and it links to curiosity!).

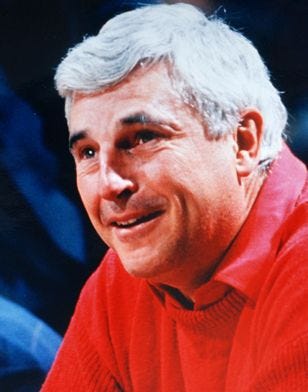

Curious About “The General”

As someone who grew up loving basketball in Indiana, I’ve been reading a lot of profiles of Coach Bob Knight since he passed last week.

This one by Eamon Brennan was my favorite.

Recent Writing

Keep Your Shirt On — The CEO of AirAsia decided to get a massage during a management meeting. What could go wrong?

Golf Swings, Sexism, and Suzanne Somers — Suzanne Somers asked for a pay rise 40 years ago. What would happen if she did that today?

Did you hear about the $78 meal at Newark Airport? It was followed by an “apology” that wasn’t worth $78. Columnist David Brooks is #sorrynotsorry.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

Poor communication costs you — money, relationships and your reputation.

This week’s case in point:

Sam Joel, a start-up founder, was forced to step down from his crypto-based charity after he made a slew of offensive comments on LinkedIn.

Although his company issued an odd apology, Joel was out the next day.

Investing in your communication skills pays dividends.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, Stay Curious!

-Beth

This is my favourite Curious Minds so far. I laughed heartily out loud THREE TIMES reading this. I AM going to share it Beth, so there!

Love this and the video, Beth! We were taught about the Streisand Effect in journalism training.