Where Did Artificial Christmas Trees Come From?

And who is the "King of the Artificial Christmas Tree"?

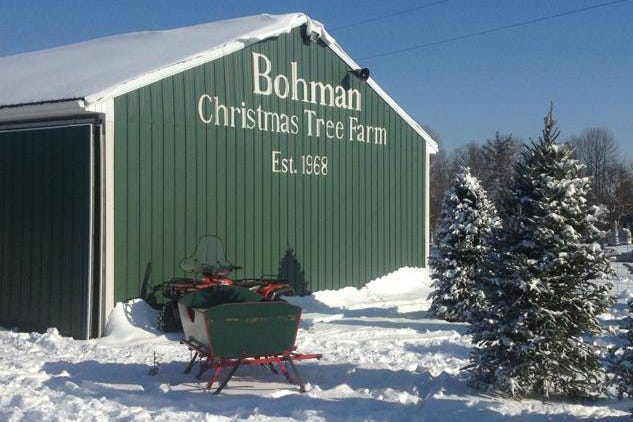

When I was a little girl, I remember getting in the back of Mom’s station wagon in December and driving to the Christmas tree farm.

My older sister and I would stomp through the snowy paths of trees, searching for the best option.

My mom would walk around the trees, inspecting them for bare patches, and once we’d agreed on the best tree (tall enough, but not too tall), a man with an axe would cut it down, and strap it to the top of the car.

Real trees were the way to go back then.

But now instead of lugging a tree along the interstate, I crawl into the eaves storage to dig out my Balsam Hill (artificial) tree.

While I used to believe “fake tree = fake Christmas”, my husband’s real allergies to pine mean we have an artificial tree at Christmas.

But, digging out the tree this year got me thinking…

Where did artificial Christmas trees come from?

I was curious…

The story of artificial trees begins with…a problem.

Back in the late 19th century, the tradition of having a live Christmas tree was popular across Germany – and beyond.

Natural Christmas trees had become so popular that demand outweighed the supply.

Faced with deforestation, the German government stepped in and limited each family to one tree.

That’s when industrious farmers stepped in, and an alternative hit the market – Goose Feather artificial trees.

The Goose Feather “tree” was created by taking a large stick and attaching metal wires or smaller sticks to it to resemble branches on a tree. Then goose feathers were dyed green and attached to the “branches” to create the image of a tree.

German families would make these trees (and variations with turkey, swan, and ostrich feathers) and sell them at Christmas markets.

When Germans immigrated to the United States, they brought their Goose Feather trees with them.

And in 1913, artificial trees were first advertised in the Sears Roebuck catalogs.

Artificial trees had berries and candleholders, and ranged in height from 17-55 inches.

The Goose Feather trees became more popular in the US over the next decade, until the growing tree farm industry began providing a greater supply of natural tree options.

As natural tree options were increasing in the US, artificial tree options were increasing in the UK.

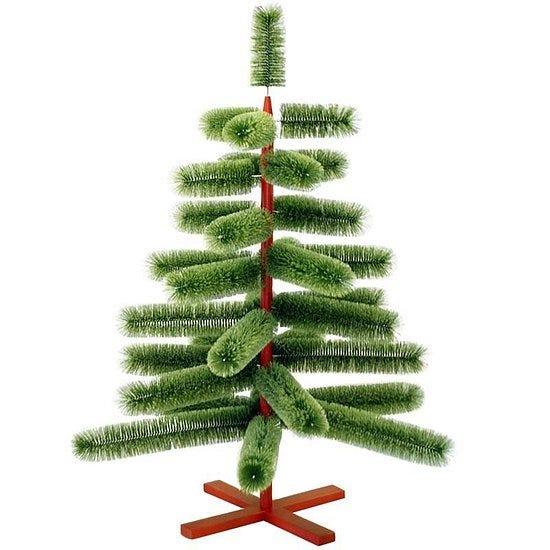

The British-based Addis Housewares Company started creating artificial Christmas trees using brush bristles. Their trees were made from the same animal-hair bristles used in toilet brushes, but they were dyed green.

Using the toilet brush “technology” allowed them to make an artificial Christmas tree that could hold more weight (and thus more ornaments) than a Goose Feather tree.

The popularity of artificial Christmas trees grew in England during World War II, as natural Christmas trees were hard to come by at the time.

Addis continued manufacturing artificial trees (as well as toilet brushes).

They also created an entirely aluminum Christmas tree, and received a patent for their “Silver Pine” in 1950.

And back across the pond, the artificial Christmas tree was starting to make a comeback in the US.

“Probably the most important moment in the history of artificial Christmas trees occurred during the late 1950s when a startling discovery was made: that brush-making machines — the kind that were used to manufacture, say, bottle brushes or hair brushes — could be adapted to make artificial Christmas trees,” Nathan Cobb reported in the Boston Globe in 1986.

In the 1950s, a New York-based company called American Brush Machinery decided to repurpose their brush machines to make artificial Christmas trees.

Their early attempts, made with green polyvinyl chloride plastic, didn’t look much like Scotch pines, and failed to catch on.

Few Americans owned green artificial trees at that time, and the aluminum trees (lit by color wheels) were the more popular artificial option.

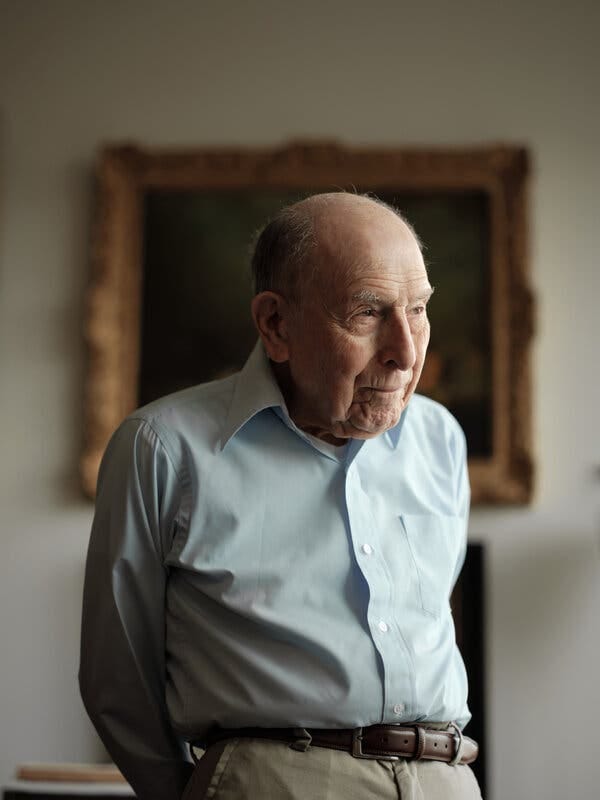

Convinced their artificial tree prospects were dead, Si Spiegel, a senior machinist at American Brush Machinery, was sent to close the factory.

But instead of closing the factory, Spiegel told his higher ups there was an opportunity.

Even though most of the management disagreed with him, Spiegel was given a meagre budget and his own division – American Tree and Wreath.

And Spiegel got creative.

He noticed the artificial trees they were producing looked fake – so he brought in real trees to study, and experimented with the machines to speed up the process.

Spiegel found a way to make his artificial trees look more realistic and also increased production – just as natural pine trees were becoming scarce in the US.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, pine trees were mostly harvested from the wild (rather than grown on a farm scale). The lack of natural pine trees meant more people were open to the artificial tree alternative – especially ones that looked more natural.

Plus, the artificial trees didn’t wither, or require the same cleaning and care of real trees.

Spiegel became an expert on artificial Christmas trees and began patenting his designs in the 1970s.

His first patent was for a hinged branch holder followed by an artificial tree that could be assembled quickly.

By the mid-1970’s, Spiegel was producing 800,000 trees a year for American Tree and Wreath.

Then in 1982, Spiegel and three of his co-workers left the company to set up Hudson Valley Tree.

In 1986, Hudson Valley Tree received a patent for the method and machine used to form the branches for their tree, and by 1988, they were one of the largest manufacturers of artificial Christmas trees in the country.

In just six years they had grown from four employees to a $25 million business with 800 employees.

“I expected a good business, but I didn’t think it would be this good,” Spiegel said in an interview in 1988.

“We originally thought we’d take the higher end of the market and sell locally to department stores and nurseries,” he said.

Spiegel credited part of his success to how much attitudes about artificial trees had changed over the years.

“When I first began manufacturing trees in the early 1960s, 95 percent of the people said they’d never have an artificial tree.”

In 1993, at age 69, Spiegel, “The King of the Artificial Christmas Tree”, sold his company and retired as a multimillionaire.

And since then, artificial trees have become a staple for many families – with the National Christmas Tree Association reporting that three-quarters of American homes had artificial trees in 2020.

The British Christmas Tree Growers' Association estimates that the Christmas trees in British homes are split more evenly between artificial and real trees.

Now 98 years old, Spiegel lives in New York City.

And even though most artificial trees in the United States are based on his designs, you won’t find an artificial tree in Spiegel’s house.

FUN FACT:

Charlie Brown killed aluminum trees.

In 1965’s Charlie Brown’s Christmas, Lucy requests a pink aluminum tree, but Charlie chooses a small real tree to protest the commercialization of Christmas.

The popularity of aluminum trees fell after the special aired.

Bonus: Si Spiegel’s history in the role of the artificial Christmas tree is not the most interesting thing about him. Check out this profile The New York Times did in December 2021 to learn how he bombed the Nazis and outwitted the Soviets during World War II and listen to this interview he did for the New York State Military Museum in 2016.

Recent Work and Writing

Is Die Hard a Christmas Movie? Yippee Ki Yay! This debate comes up every year, so I’ve investigated what makes a Christmas movie - and where Die Hard stands.

The ONE thing that matters most when you’re giving a speech — Trust me, folks. If you’re giving a speech or a presentation, this is where you need to focus.

How Beth Collier uses mmhmm to power connected, clear communication — Find out my favorite app to make coaching and workshops more fun.

Is this sexist — or sloppy? Diane Ladd deserved better

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And look at the way New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern used her communication skills to school a reporter this week.

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

No way, Charlie Brown killed the aluminium tree?! A very interesting read.

Very informative. I have to laugh at the color wheel. So high tech!