"I Cannot Tell a Lie..."

But I can make up a story!

I’ve been thinking about US presidents this week…and the stories we tell about them.

Most US presidents I learned about in school were limited to a paragraph or two in a textbook (though some — like the three pictured above — were more popular than others).

I was taught that our former presidents were men worthy of admiration — they were hard-working, brave, and honest.

Honesty was a core trait of our country’s early (and most beloved) leaders.

Abraham Lincoln’s nickname was “Honest Abe” after all.

Our 26th president Theodore Roosevelt said, “Honesty, rigid honesty, is a root virtue; if not present, no other virtue can atone for its lack.”

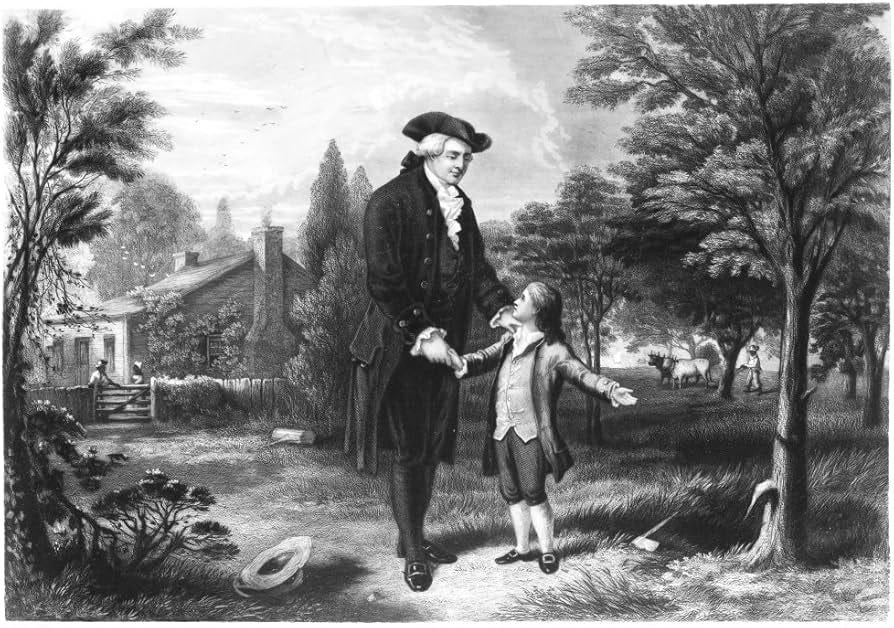

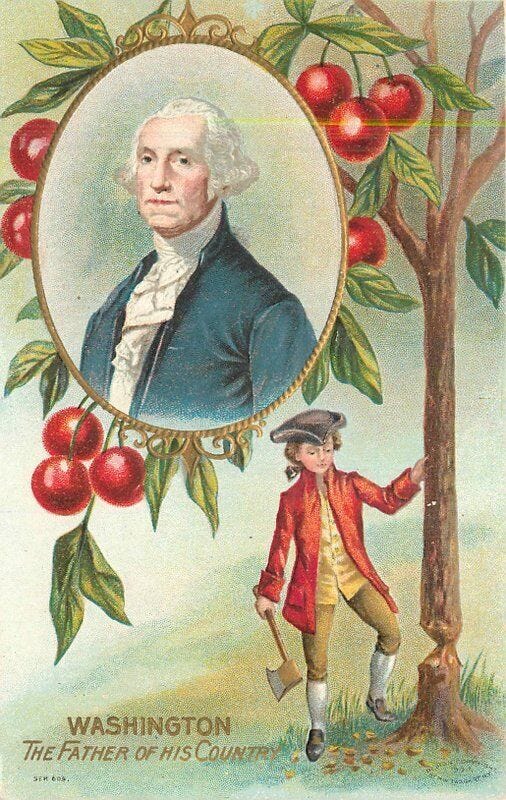

And the story I remember learning at an early age about the most famous president of all — George Washington — involved a cherry tree, and a young Washington famously saying, “I cannot tell a lie.”

In case you are not familiar with it, here’s the story I was taught as a child:

Once upon a time, a young boy named George Washington received a hatchet as a gift.

He used it to cut down (or at least damage) his father’s cherry tree.

When his father discovered the damaged tree, he was angry.

Though George feared he would be in trouble for what he had done, he was brave and honest, and told his father, “I cannot tell a lie” and confessed.

Washington’s father was so proud of his son’s honesty that George was not punished.

The End

The moral of the story was that we should always be honest.

(And this story proved that George Washington was admirable — even at a young age)

According to The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, “the cherry tree myth is one of the oldest and best-known legends about George Washington.”

Myth? Legend?

No, the Cherry Tree story I was told was not presented as a myth – but as fact. This was a true story – and it demonstrated how important honesty was to our first President.

(And hey, it’s a nice message – and in the grand scheme of things, not the worst story you could feed formative young minds).

But where did the story come from – and why was it created?

I was curious…

When George Washington died in 1799, the American people were well-aware of Washington the General and Washington the President.

But very little was known about George Washington outside of his public life.

And this was a gap a traveling minister and bookseller named Mason Locke Weems sought to fill.

“Washington you know is gone!” Weems wrote to Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey in January 1800.

“Millions are gaping to read something about him...My plan! I give his history, sufficiently minute…I then go on to show that his unparalleled rise and elevation were due to his Great Virtues.”

Writing about Washington gave Weems (more popularly known as “Parson Weems”) an opportunity to use Washington to teach morality – and an opportunity to make money.

“In most of the elegant orations pronounced to his praise, you see nothing of Washington below the clouds – nothing of Washington the dutiful son – the affectionate brother – the cheerful school-boy – the diligent surveyor – the neat draftsman –the laborious farmer – the widow’s husband – the orphan’s father –the poor man’s friend,” Weems wrote.

“No! This is not the Washington you see; ‘tis only Washington, the HERO, and the Demigod – Washington the sun-beam in council, or the storm in war.”

Weems was confident the public wanted to know more about Washington, and his book would be affordable, and play to the patriotic enthusiasm in the country.

Carey agreed — and in 1800, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues, and Exploits of General George Washington by M.L Weems was published.

Interestingly, the first version published did not include the story about Washington and the cherry tree.

But the book proved popular, even if Weems’ “facts” were questionable.

The September 1800 edition of The Monthly Magazine and American Review called Weems’ biography “as entertaining and edifying matter as can be found in the annals of fanaticism and absurdity.”1

But Weems understood his audience — specifically low-income and middle-income readers in Virginia, Maryland, Georgia and the Carolinas — and he continued to revise his biography of Washington to give them what they wanted.

What started as an 80-page pamphlet became a 200+ page book — full of colorful anecdotes and stories.

And Weems’ biography of the Father of Our Country became a bestseller.

In 1806, he added the story about the cherry tree, when the fifth edition of his book was published (now under the title The Life of George Washington).

Weems’ stressed the importance of honesty in Chapter 1, sharing the lesson young George was taught by his father, Augustine:

“Truth, George,” said he, “is the loveliest quality of youth. I would ride fifty miles, my son, to see the little boy whose heart is so honest, and his lips so pure, that we may depend on every word he says.”

Honesty was so important to Augustine that he told young George he would “give him up, rather than see him a common liar.”

Instead, as Weems wrote, Augustine taught George to always tell the truth:

“You must never tell a falsehood to conceal it; but come bravely up, my son, like a little man, and tell me of it: and instead of beating you, George, I will but the more honour and love you for it, my dear.”

This set Weems up nicely for what came next, something he claimed was “too valuable to be lost, and too true to be doubted.”

Weems claimed the story was told to him by a distant (and unnamed) female relative of the family who “as a girl had spent time with the Washingtons.”

The Original Cherry Tree Story

Here is the story Weems recounted in his book:

“When George was about six years old, he was made the wealthy master of a hatchet! Of which, like most little boys, he was immoderately fond, and was constantly going about chopping every thing that came in his way.

“One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother’s pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don’t believe the tree ever got the better of it.

“The next morning the old gentleman, finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favourite, came into the house; and with much warmth asked for the mischievous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him any thing about it. Presently George and his hatchet made their appearance.

“George, said his father, “do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry tree yonder in the garden?”

“This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet.”

“Run to my arms, you dearest boy, cried his father in transports, run to my arms, glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son is more worth than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold.”

But there is no proof that this actually happened.

As Washington biographer Henry Cabot Lodge would write years later, there was “nothing intrinsically impossible” about Weems’ cherry tree story, but that it was “hopelessly and ridiculously false.”

But that didn’t stop people from reading — and repeating — the story of Washington and the cherry tree.

In the 1830s, William Holmes McGuffey began including a version of the cherry tree story in grammar school textbooks.

McGuffey’s Readers sold over 120 million copies and remained in print for nearly a hundred years, reinforcing the idea of George Washington as an ideal role model.

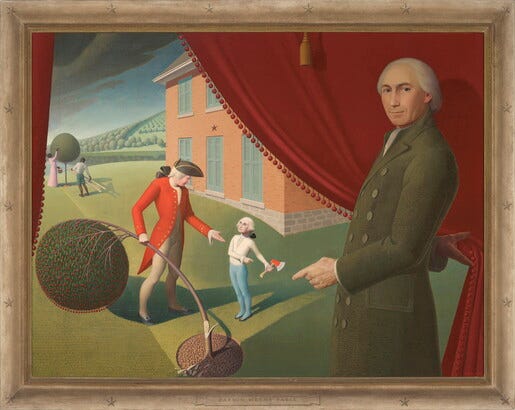

While the American public elevated and celebrated Weems’ view of Washington, art history shows us that there were some cynics.

In 1939, artist Grant Wood2 painted “Parson Weems’ Fable.”

The painting shows Mason Locke Weems pulling back the curtain to reveal the scene of a young George Washington (with the face of the adult Washington we recognize from the $1 bill) holding a hatchet while his father holds the damaged cherry tree.

And though many biographies of Washington have been written, the cherry tree story is not something you’ll find verified in them.

So it would seem that I — and millions of other children — were misled when we were told the story of George Washington and the cherry tree.3

But, writing this in the shadow of the 2025 presidential inauguration, I reflect on a quote attributed to Abraham Lincoln,4 in Henry C. Whitney’s Life on the Circuit with Lincoln.

When some attorneys on the Eighth Judicial Circuit “scoffed at the common belief in George Washington’s infallibility”, Lincoln protested, saying:

“Let us believe, as in the days of our youth, that Washington was spotless.

“It makes human nature better to believe that one human being was perfect—that human perfection is possible.”

In case you’re curious, here’s a short video that explains more on Grant Wood’s painting, Parson Weems’ Fable:

One more thing…

I also remember being told that George Washington had dentures made out of wood.

Not true, according to Mount Vernon.

His dentures may have been stained, but they weren’t made of wood.

“Throughout his life, Washington employed numerous full and partial dentures that were constructed of materials including human, and probably cow and horse teeth, ivory (possibly elephant), lead-tin alloy, copper alloy (possibly brass), and silver alloy,” they report on their website.

But not wood.

Apparently, Washington didn’t wear a wig or skip silver dollars across the Potomac either…

What other lies was I told?!5

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

Poor communication costs you — money, relationships and your reputation.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, Stay Curious!

-Beth

I read the full review from 1800. The author was definitely not a fan of Weems’ writing! “It is regretted that the precious fabric [sic] ef his character [Washington] should be touched by rude and disordered hands.”

You are probably familiar with Wood’s 1930 painting “American Gothic”

Anyone else find it ironic that the story Weems used to illustrate the importance of honesty was (more than likely) a lie?

Lincoln is believed to have been one of the readers of Weems’ biography of Washington.

Education sure was different when I was growing up. We didn’t have the internet to supplement our learning - just the World Book Encyclopedia!

This was well-timed, Beth. Always enjoy your work.