Hello!

Though Mariah Carey officially kicks off the Christmas season on November 1st, I don’t hang any decorations or listen to Darlene Love until Thanksgiving is over.

I don’t even want to engage in the annual “Is Die Hard a Christmas movie?” debate until December. (Short answer: YES, it is absolutely a Christmas movie).

But on November 30, I saw a post on LinkedIn that made me engage in the Die Hard debate a day earlier than I planned.

But one comment on the post caught my eye.

It said that Jingle Bells was not written as a Christmas song.

Was that true?

I was curious…

When I began researching this piece, I quickly found articles that confirmed Jingle Bells was not written for Christmas.

It was written for Thanksgiving, they claimed.

For a church service.

By a man named James Lord Pierpont.

“That was easy!” I thought. “I’ll be able to write this story in no time!”

Not so fast…

I decided to do a bit more digging, and discovered an article that said Jingle Bells was “a little bit racy.”

Eh?

I kept digging — and the more I looked, the more complicated this story became.

So, let’s start with what we do know.

James Lord Pierpont was born in Boston in 1822.

In 1832, when James was attending boarding school in New Hampshire, he wrote a letter to his mother about taking a sleigh ride in the snow.

And in the 1850s, he wrote a song called One Horse Open Sleigh, that he would copyright in 1857.

He would then re-copyright in 1859 as ‘Jingle Bells or One Horse Open Sleigh.’

The exact year that he wrote the song is debated.

And where the song was written is also debated.

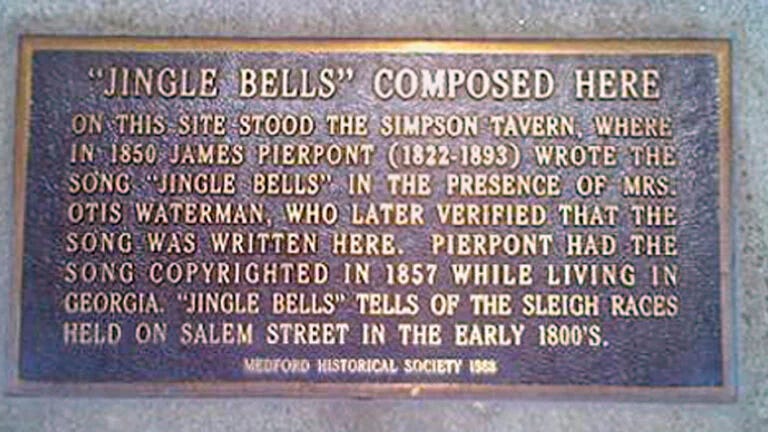

Medford, Massachusetts (just outside Boston) claims Pierpont wrote Jingle Bells at the Simpson Tavern in 1850, and that the song chronicles the sleigh races held on the town’s Salem Street in the 1800s.

They have a plaque to mark the location that also claims a witness – Mrs. Otis Waterman – verified the song was written there.

But, despite Medford displaying a plaque to support their claim, I’m not convinced.

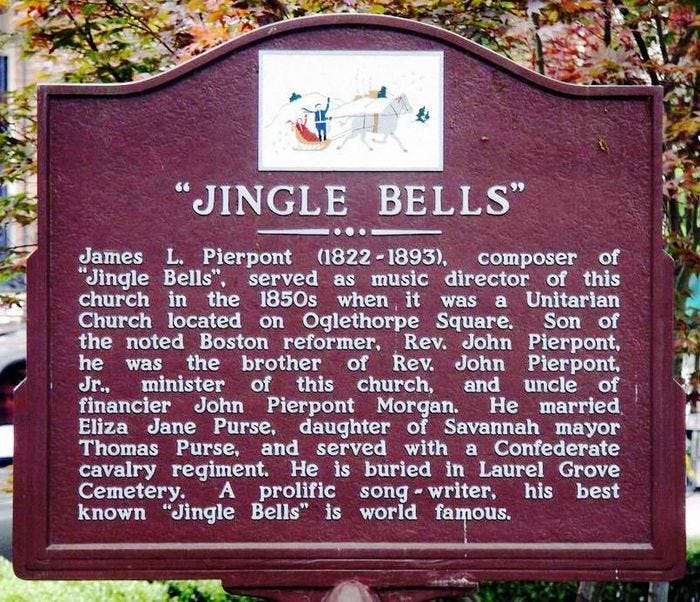

Because Savannah, Georgia also has a plaque (or rather, a sign).

Pierpont may have spent much of his youth up north, but he moved to Savannah in the 1850s.

And as Medford’s plaque acknowledges, Jingle Bells (or rather, One Horse Open Sleigh) was published on September 16, 1857 — when Pierpont was living in Savannah.

At that time, Pierpoint was working as the music director of the Unitarian Church where his brother, John Pierpont, Jr., was the minister.

Georgia historians disagree with Medford’s claim to the song, suggesting that Pierpont wrote Jingle Bells in Savannah when he was feeling nostalgic for his upbringing in New England.

The debate even led to a feud between Medford and Savannah in the 1980s, as both towns claimed ownership of the song.

So, which town is right?

To get to the bottom of that, I wanted to find out more about James Lord Pierpont.

One source I found said he was a “rebellious musician with a bad reputation.”

Another said he “wasn’t much of a family man.”

Others were more blunt.

James Lord Pierpont was a “wanderer” who was “kind of a jerk” and a “peripatetic1, perennially broke ne’er-do-well.”

In 1994, one unnamed historian told the Medford Citizen that James Lord Pierpont was a “complete loser.”2

Even his great-granddaughter Constance Turner described him as “quite the free spirit.”

So what’s the story?

James grew up in New England, the fifth of six children, in a staunch abolitionist family.

His father, John Pierpont, is considered the “poet of the abolitionist movement,” and spent most of his life working as a minister in Boston and New York.

But instead of following his father’s example of temperance and spirituality, James appears to have rebelled, running away in 1836 to sea on a whaling ship.

He returned to Troy, New York (where his father was working as a minister) in 1845 and got married to Millicent (Millie) Cowee.

The couple had two children.

But James didn’t stay long.

In 1849, James left his wife and children behind to seek riches out west during the California Gold Rush.

Letters he wrote to his father in 1851 detailed his troubles getting — and keeping — a job.

He found no riches out west, and returned —broke —to Medford, where his father was working as a minister.

And then James – the son of a staunch abolitionist – began writing songs for minstrel shows.

The first of these appears to be The Returned Californian3, published in 1852.

The lyrics might clue us in to James Lord Pierpont’s experience out west.

Oh, I’m going far away from my Creditors just now,

I ain’t the tin to pay ‘em and they’re kicking up a row;

I ain’t one of those lucky ones that works for ‘Uncle Sam,’

There’s no chance for speculation and the mines ain’t worth a (‘d--’) Copper.

There’s my tailor vowing vengeance and he swears he’ll give me Fitts,

And Sheriff’s running after me with pockets full of writs;

And which ever way I turn, I am sure to meet a dun,

So I guess the best thing I can do, is just to cut and run.

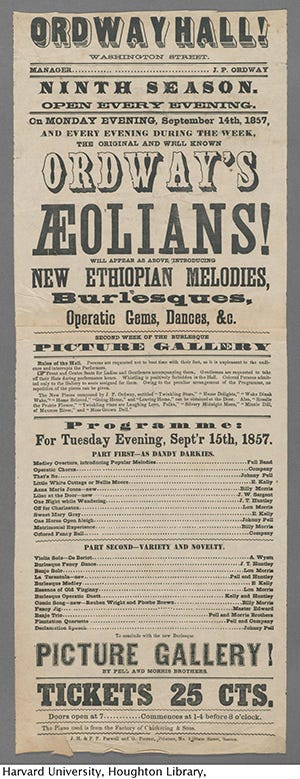

It was performed by Ordway’s Aeolians, a blackface minstrel troupe organized by John Ordway.

Boston University history professor Kyna Hamill discovered that Pierpont composed at least 13 songs for minstrel troupes in Boston and New York between 1852-57.

And one of these songs was called One Horse Open Sleigh.

“Sleigh songs were having a moment, and Pierpont, who had failed in so many other professional ventures, simply needed the work,” Hamill wrote in 2017.

Pierpont’s song talked about taking a girl out on a sleigh ride — and sleighing fast.

It wasn’t an original idea — or an original song.

Sleigh riding was a popular leisure activity in the Boston area – and a popular theme for minstrel shows that featured white performers wearing blackface.

Pierpont’s lyrics certainly bear a resemblance to others performed at the time, such as The Merry Sleigh Ride, published in 1844, and Buckley’s Sleighing Song from 1853.

There were several popular minstrel songs involving sleighs, such as De Merry Sleigh Bells, Darkey Sleigh Ride Party, and The Darkey Sleighing-Party where exaggerated dialect was written for blackface performance.

Hamill notes that Pierpont’s melody conforms to the baseline of most minstrel music, but that “there is nothing original or local about its subject.”

“Everything about the song is churned out and copied from other people and lines from other songs,” Hamill wrote.

“He’s making money.”

Hamill discovered that blackface minstrel performer Johnny Pell sang Pierpont’s One Horse Open Sleigh during an Ordway’s Aeolians performance in September 1857.

And Pierpont’s connection to Ordway is evident by the “To John P. Ordway, ESQ,” dedication at the top of the sheet music for One Horse Open Sleigh:

But One Horse Open Sleigh did not make James Lord Pierpont rich.

Following the death of his first wife Millie in 1856, James abandoned his two children and headed south.

He returned to Savannah, Georgia where he had lived in 1853, and worked as music director at the church where his brother John Pierpont, Jr. was pastor.

In August 1857, James married Eliza Purse, daughter of Savannah’s mayor, and fathered more children.

Census records indicate that his oldest daughter with Eliza was born in 1854, three years before they wed (and two years before his first wife died).4

Perhaps the records are wrong, or perhaps that’s further evidence that James wasn’t the a “family man” his father would have expected.

And James’s family drama was far from over.

The abolitionist views of the Unitarian Church in Savannah became more unpopular as tensions rose between the North and South.

The church closed in 1859, and James’s brother, Rev. John Pierpont Jr., returned to the North.

But instead of joining his father or brother, James remained in Savannah, and joined the Confederate cause.

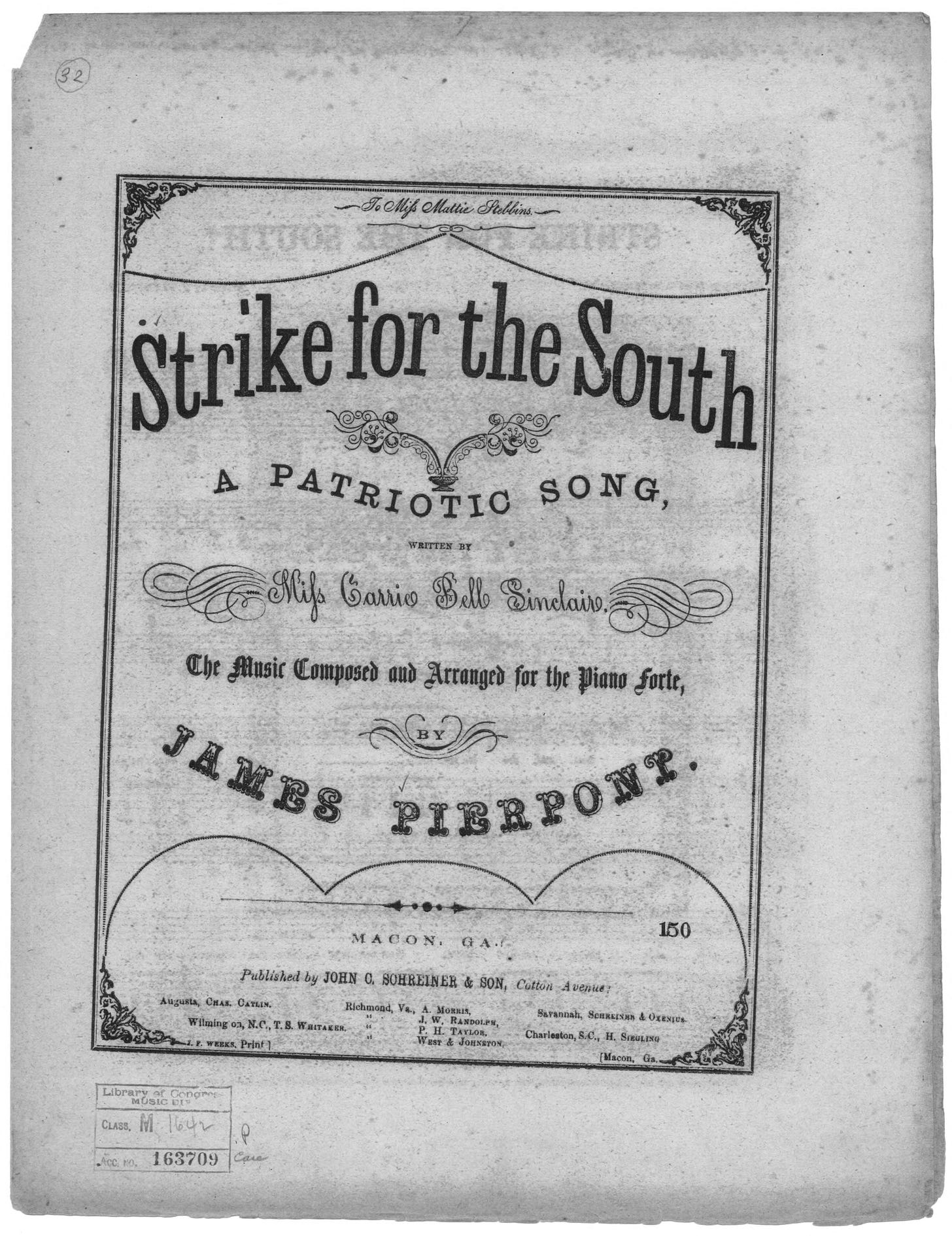

While his father served as a chaplain in the Union Army, James was a private in the Lamar Rangers, and even wrote songs for the Confederacy, including We Conquer or Die (1861), Our Battle Flag (1862), and Strike for the South (1863).

James Lord Pierpont survived the war — but died before Jingle Bells became famous.

By the late 1800s, Jingle Bells was often published without attribution to James Lord Pierpont.

And the song’s attribution to “J Pierpont” led to more confusion, with some later interpreting the author to be James’s poet father, John.

James died in 1893, five years before the first recording of Jingle Bells (by the Edison Quartet).

Benny Goodman would later record Jingle Bells in 1935, and Glenn Miller would release his rendition in 1941.

Fifty years after James Lord Pierpont died, Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters would turn Jingle Bells into a holiday staple.

But wait, why was Jingle Bells considered racy?!

Sleigh riding wasn’t just an activity for transport and amusement in the 1800s, it was also used for courtship.

A sleigh ride enabled couples to sit close and under cover, away from a chaperone.

Though most of us are familiar with the first verse and chorus, Pierpont’s Jingle Bells actually has four verses.

The lyrics tell a story about taking a girl (who verse two reveals is named Fannie Bright) on a sleigh ride – and sleighing fast.

Pierpont’s lyrics suggest “two forty speed” — equivalent to 22.5 mph. (For comparison, carriages at that time tended to travel around 8mph).

The fourth verse specifies to “go it while you’re young” and “take the girls to night and sing this sleighing song.”5

While some articles would have you believe Jingle Bells was written for a church service, these lyrics suggest otherwise – especially given the time period.

And this is a point that historians from both the North and South seem to agree.

“The references to courting would not have been allowed in a Sunday school program of that time such as ‘Go it while you’re young’,” Savannah historian Margaret DeBolt wrote.

So, where was Jingle Bells written?

It’s not an easy question to answer.

It could have been Medford. Or Savannah.

Hamill has suggested Jingle Bells may have been written while Pierpont was staying at a boarding house in Boston.

Or maybe it was written when Pierpont lived out west.

Who knows?

But in a story full of debate, it seems we can surmise that it is unlikely Jingle Bells was written for a church service — or as a Christmas song.6

What I know for sure is that this story has reminded me why it’s so important to dig when you’re researching a story — and dig deep.

One more thing…

This appears to be true!

On December 16, 1965, astronauts from Gemini 6 played a little prank on NASA — reporting “an object” traveling from north to south.

The tense report was then broken by the sound of Jingle Bells coming from Gemini 6, played on on a tiny harmonica by Wally Schirra, accompanied by small sleigh bells played by Tom Stafford.

“Wally came up with the idea,” Stafford told Smithsonian magazine in 2005.

“He could play the harmonica, and we practiced two or three times before we took off, but of course we didn't tell the guys on the ground.”

“We never considered singing, since I couldn’t carry a tune in a bushel basket.”

This was the first musical interlude from space.

You can listen for yourself:

And speaking of listening…

Here’s the version you’ve probably heard by Bing and the Andrew Sisters:

Benny Goodman’s Jingle Bells from 1935

Glenn Miller’s Jingle Bells from 1941

And here’s a recording of Jingle Bells from 1898:

And one other thing I learned…

In case you’re thinking, “That name James Pierpont feels familiar”…

James Lord Pierpont may not have been rich, but his nephew sure was!

James’s sister Juliet married banker and financier Junius Morgan in 1836.

They had five children together; the eldest was John Pierpont Morgan, aka JP Morgan7.

It’s A Great Time to Celebrate Die Hard…

Jingle Bells wasn’t written for Christmas, and neither was Die Hard…

But that doesn’t mean they aren’t part of Christmas today!

Not only is Die Hard a Christmas movie, it’s also a movie full of inspiration for business and life.

(Yes, really).

And all week, I’ve been sharing a bit of daily Die Hard inspiration on LinkedIn as I celebrate “Die Hard Week” (a totally real thing that I definitely didn’t make up three years ago).

Check out my LinkedIn page to see what gems Die Hard provides.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap massive rewards – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

I had to look this one up - it means “travelling from place to place, in particular working or based in various places for relatively short periods.”

I could not get my hands (or eyes) on a copy of this, but based on amy research of James Lord Pierpont, I find it credible that a historian would have made this assessment.

Listening to this song I can hear traces of both “Oh Susanna!” (written in 1846) and “Jingle Bells”

This seems possible, given “not a family man” James was in Savannah in 1853

Very racy for the 1850s…

Though perhaps an edited version was performed at a church service?

Quite the successful banker and financier himself…

More great storytellin’, Beth! I was born on Christmas Day, so this definitely jingled my bells. ✍🏻Write on! ~GSD&Me

Checked wikitree and I am 18 degrees of separation from this philanderer!