"Saucy" and "The Bad Boy": A Tale of Two Platypuses

Yes, a reporter called a platypus "saucy." I had to find out why.

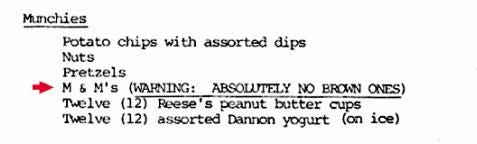

Before we begin… On February 5, 2021 I sent my first issue of Curious Minds — where I was curious what Van Halen had against brown M&M’s when they were on tour.

This is an excerpt from their tour rider (the list of all the things a concert venue needed to do and provide before a show):

Fifty three people opened the email I sent.

That’s right, 53.

But since then, I’ve shared 150 stories, like clockwork, every Friday at 11 am (London time).

And more than 53 people open my emails now.

I don’t take your time for granted, and work hard to bring you stories that are interesting, and/or fun.

So thanks for being here — and for sharing the joy of curiosity!

And while I try not to play favorites with my stories, I’m really excited to share this one with you today.

It took me deep into the newspaper archives — and I hope you enjoy reading it!

February is the month full of love stories.

But I wouldn’t describe today’s story as a love story.

It feels like a story from a soap opera — except it’s about platypuses.

That’s right, platypuses, the animal you might remember if you had those Wildlife Treasury cards when you were a kid.

But recently I stumbled upon a story from the 1950s that described a platypus as “saucy.”

And another as a “bad boy.”

What makes a platypus “saucy”?

Or a “bad boy?”

I was curious.

Our story begins on July 14, 1922, when something exciting arrived at the Bronx Zoo in New York.

A new animal – all the way from Australia.

It was a platypus: a duck-billed, furry, web-footed animal that was described as the connecting link between a mammal and a bird.

It had “long been the desire” of the Bronx Zoo to obtain one of these mysterious creatures that could only be seen in Australia or Tasmania.

Five platypuses made the journey, but when their ship arrived in San Francisco, only one platypus had survived.

That platypus continued his journey to New York, where he was welcomed with a party – one that he was “too shy” to enjoy, according to the New York Times.

Even though the platypus had reportedly eaten a worm “with gusto”, the Zoo now had the challenge of keeping this 20-inch platypus alive.

And sadly, that platypus died 49 days later.

It would be another 25 years before a platypus would be seen in the United States again.

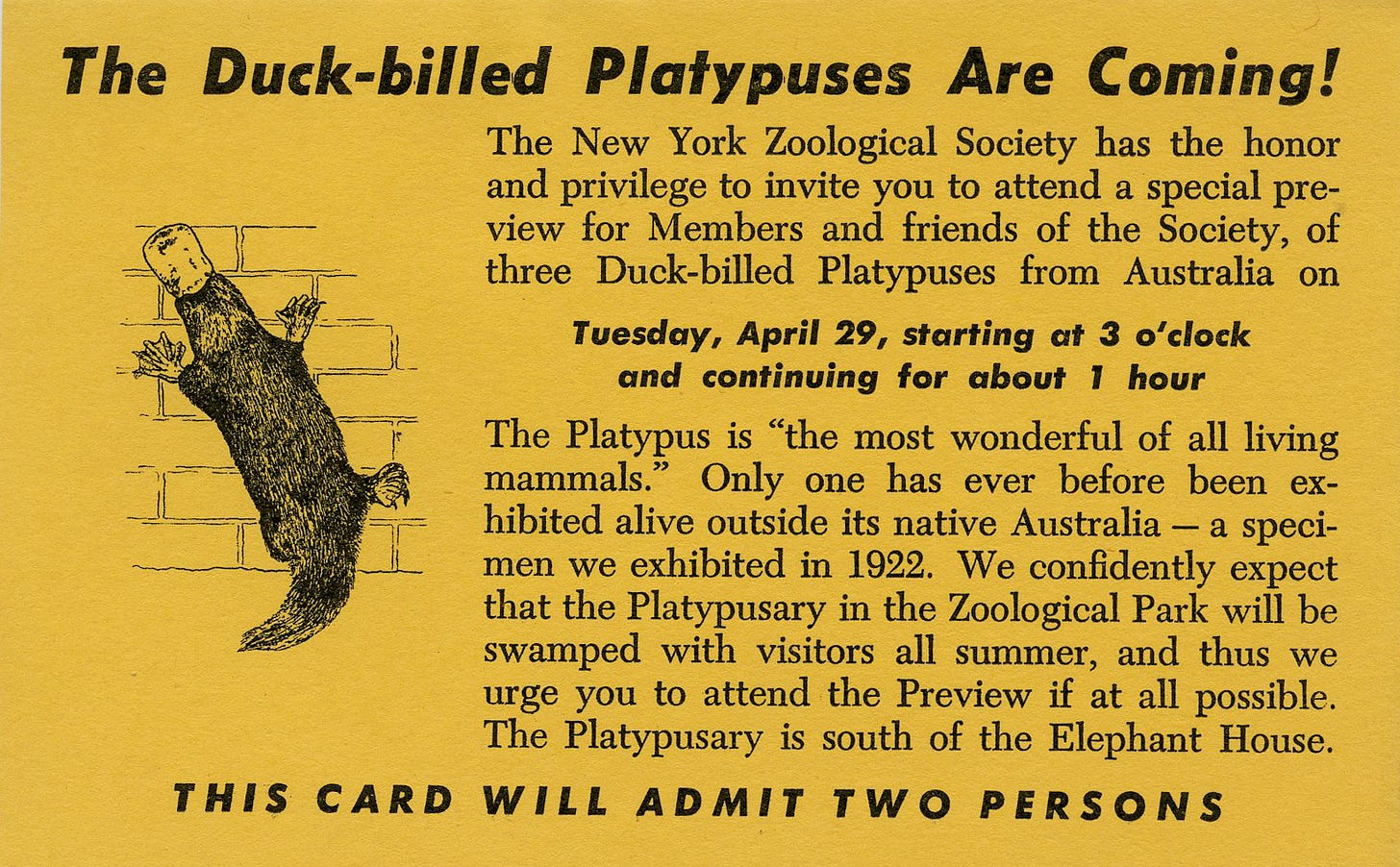

But on April 25, 1947, three platypuses – Betty, Cecil and Penelope – made the journey from Australia to make their new home at the Bronx Zoo.

To prepare for their arrival, the Bronx Zoo created a special platypusary, built to the specifications provided by Australian zoologist David Fleay, the authority on the unusual platypus.

The 9-foot-by-7-foot enclosure included a small swimming pool and private burrows.

While it was a coup for the Bronx Zoo to be the only place outside Australia to exhibit platypuses, they wanted more.

More platypuses.

A platypus had recently been born in captivity for the first time, and the zoo hoped that by bringing two females and one male to the Bronx, they might be able to grow their platypus exhibit as well.

But then Betty died in a heatwave in 1948.

And the zoo put all its hopes of a growing platypus exhibit on Cecil and Penelope.

There was just one problem.

Penelope didn’t like Cecil.

According to Time:

“On a warm spring day in 1951, they placed Cecil in Penelope’s half of the platypusary. As soon as she saw him, she took evasive tactics, dashing into the water, rolling over and over and scratching furiously with all of her 20 sharp claws. Cecil seemed interested, but decided that he was not welcome. He made no overtures.”

Zoo staff tried again in the spring of 1952.

Cecil tried to get Penelope’s attention, by “grabbing her flat tail in his duckbilled, toothless mouth” and holding on while she “dragged him around the pool in slow circles.”

But Cecil weighed four pounds, twice as much as Penelope.

Her tail hurt, and “she didn’t want him around.”

Zoo official William Bridges told the Associated Press that Penelope “actively resented Cecil’s overtures.”

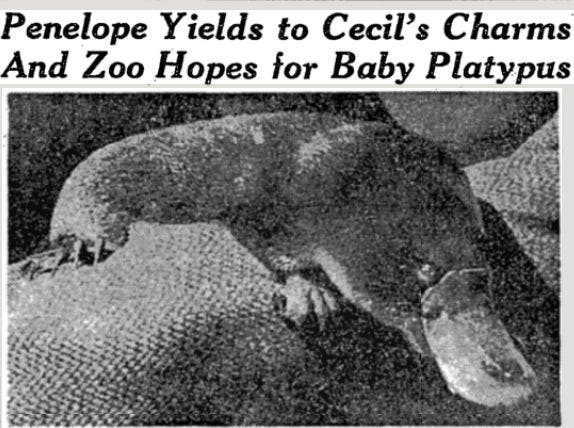

Then in June 1953, something changed.

Penelope began to scratch at the wooden barrier separating her from Cecil, as if she wanted to see him.

The zoo staff put the two platypuses together, and hours later Cecil was holding on to Penelope’s tail with his bill as she towed him around the water tank.

For a platypus, this was a potential sign of mating.

And a few weeks later, Penelope’s appetite increased.

When the curators gave her eucalyptus leaves, Penelope took them into her burrow.

Zoo staff took this as a sign that she was building a nest for babies.

The New York Times reported that after a “stormy courtship”, the zoo was optimistic, but cautious.

They closed the platypusary for an indefinite period of time, just to be safe.

On July 9, 1953, Penelope retired to her burrow and stayed there for six days. When she emerged, she ate an enormous meal, then returned to her burrow.

A platypus normally lays two eggs at a time, which hatch 6-10 days later.

Zoo officials were “reasonably certain” she’d given birth.

But now they had to wait.

Baby platypuses don’t tend to leave their burrows for 3-4 months.

And during this time, Penelope continued eating huge quantities of worms and larvae.

But as the fall weather turned cold, the zoo needed to relocate the platypuses inside for the winter.

With no sign of any baby platykittens1, the zoo made the decision to dig into the burrow to extract the babies.

Such a momentous occasion – the first platypuses born in captivity outside of Australia – drew a lot of attention.

More than 50 newspaper reporters and photographers were there as the zoo staff dug into the dirt.

The New York Times reported that “workers surrounded by excited and smiling officials started to sift the earthen bank” at 8:30 am.

But by 2:15 pm, they had given up.

They discovered a network of burrows, and Penelope.

But no baby platykittens.

There were no eggs, no nest, or no babies, and they declared that Penelope was not a mother after all, “only a faker.”

Zoo staff were shocked.

The proof that Penelope had been pregnant was there – and despite her increased food consumption, she had actually lost weight.

How else could it be explained?

David Fleay told reporters he felt “sure that remains of young, or eggshells, would be found if Penelope’s earth bank was carefully sifted.”

But the press decided she was a “brazen hussy” who had fooled everybody.

Zookeepers said they had been duped, and accused her of “posing as an expectant mother just to lead a life of luxury on double rations.”

“What a racket she was working. Getting double rations for five months. No more of that for her,” one said.

If Penelope had ever felt any romantic feelings toward Cecil, by the following spring, they was gone.

In May 1954, The New York Times reported that Penelope and Cecil did not act like a “betrothed couple.”

“Cecil snapped at Penelope. Then Penelope turned away disdainfully,” they wrote.

Penelope and Cecil would not give the Bronx Zoo any platykittens that year – or ever.

They remained in the Bronx Zoo – and out of the news – until July 26, 1957.

That’s when Penelope disappeared.

It wasn’t clear how she’d escaped the platypusary, but zookeepers were convinced they knew why she fled – to escape Cecil.

“Cecil had been relentlessly pursuing her to the point of harassment, going so far as to wriggle into her section of the enclosure even after they’d been separated.”

But how did she get out? And where did she go?

Zoo workers were stumped, and though they scoured the ponds and streams, they found nothing.

On September 17, they officially ended the search, and said Penelope was “presumed lost and probably dead.”

The hopes of mating Penelope and Cecil were over, but there was more bad news to come.

On September 18, one day after the zoo gave up their search for Penelope, Cecil died.

Cecil would be described in the press sympathetically, as the platypus who died from a broken heart.

Penelope, by contrast, was described as “one of those saucy females who like to keep a male on a string.”

In March 1958, the Bronx Zoo announced that David Fleay would be bringing three more platypuses to New York.

Making the first transocean platypus flight, Fleay brought Pamela, Patty, and Paul from Sydney to New York.

The platypuses were described as “proper, punctilious, and proficient.”

While the Bronx Zoo managed to keep “saucy” Penelope and “bad boy” Cecil alive for years, sadly neither Pamela, Patty and Paul survived a year.

The Bronx Zoo announced that they would not import any more platypuses.

And for 50 years, there were no platypuses to be seen in the United States.

But, in 2019 platypuses returned to the US.

Two platypuses were flown from Australia to make their new home at the San Diego Zoo — and if you can’t make it to California, you can check them out on the zoo’s “Platypus Cam”.

But are these platypuses saucy, proper, or punctilious?

The San Diego Zoo isn’t saying.

One more thing…

The Bronx Zoo wasn’t the only one to request a platypus from Australia…

In February 1943, in the midst of the Second World War, Prime Minister Winston Churchill demanded that a live duck-billed platypus be sent from Australia to Britain.

He actually asked his Australian counterpart, John Curtin, to send him six platypuses.

Though David Fleay (yes, the man you read about in the story above) advised that the platypuses would not survive the journey to Britain, a “vigorous male” dubbed “Winston” was sent.

He died shortly before arriving in Britain.

Churchill sent this telegram to Australia’s foreign minister Herbert Evatt regretting the loss of (platypus) Winston, and advising that the animal would be stuffed.

How about that?

Recent Work and Writing

Enough of the Ghosting — It may be more common these days, but that doesn’t mean it’s OK.

Communication Wonders & Blunders — Find out which communication moments from CEOs, politicians, entertainers, and companies caught my attention in January — and what we can learn from them.

Remember When a Smoking Camel was Scary? I do, and I’d take Joe any day over what I read is happening to CHILDREN on the platforms owned by Meta.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

How much?

Well, look at the news.

Or look at the examples I collected in January alone!

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap massive rewards – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

Yes, that’s what they are called

Justice for Penelope!!

WILDLIFE TREASURY CARDS!!! Oh, how I coveted these...