Hello there…

I have sat down in front of my computer more than a few times this week to write this week’s story — but just couldn’t get excited about any of my ideas.

Let’s face it — the US Election has dominated a lot of the news (and some of our thoughts) for a while.

And when I read that thousands had visited the grave of Susan B. Anthony and covered it with “I Voted Today!” stickers, I started thinking about the history of women’s suffrage in the US.

Little was said about women’s suffrage in my history classes.

I imagine that’s the case for a lot of my fellow Americans.

Even the Ken Burns’ documentary focused on just two suffragists1 — Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

But, as I discovered through my research, Anthony and Stanton were part of a “triumvirate” that led the “radical wing” of the women’s rights movement.

And a triumvirate indicates three people — so who was missing?

I was curious…

As far as US suffragists go, Susan B. Anthony may have the most name recognition.

Not only do I remember her from US history class, she also was famous enough to get her own dollar coin.

While I am familiar with the name Elizabeth Cady Stanton, I didn’t know much about the person.

But the third member of the Triumvirate – Matilda Joslyn Gage – was not a name I was familiar with at all.

So who was she?

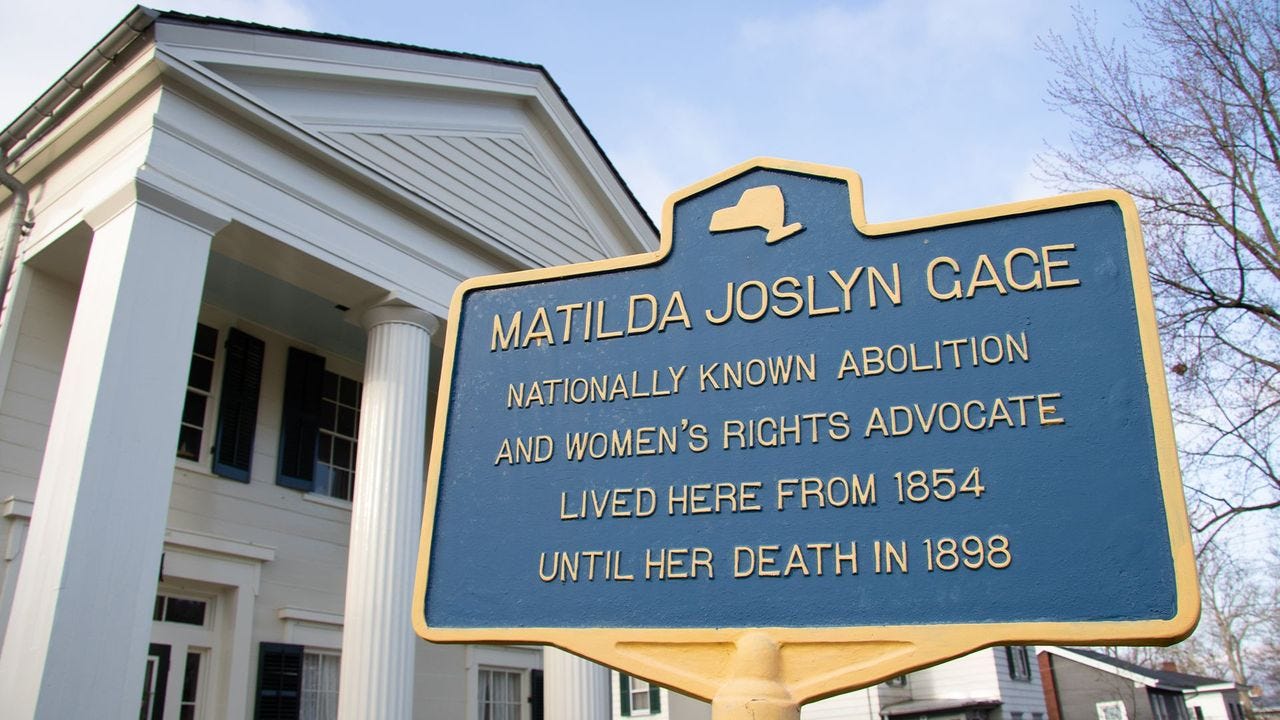

Matilda Joslyn was born in Cicero, New York on March 24, 1826, and grew up in a liberal, intellectual household.

Matilda’s father, a doctor, taught his daughter Greek, mathematics, and physiology at home, while her mother passed on a passion for history and research.

Her parents were also abolitionists, and their home was a station on the Underground Railroad.

In 1845, Matilda married Henry Gage, a local merchant who ran a dry goods store. They had five children together – four who lived to adulthood.

Matilda was a bright woman, who believed passionately in abolishing slavery – and began sharing her views in articles she wrote for various newspapers from the 1850s.

And like her parents, she offered her family home as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and signed a petition stating she would face a 6-month prison term (and a $1000 fine) rather than obey the Fugitive Slave Law.

Gage’s activism that started with abolishing slavery then extended to advancing women’s rights.

In 1852, she spoke at the National Woman’s Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York, and attended most of the annual conventions that decade.

It was during this time that she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who, like Gage, were considered more “radical.”

The three women were at the forefront of the suffrage movement, and worked together organizing conventions, circulating petitions, and writing editorials and newspaper articles.

Gage was a prolific writer and held various leadership positions, often working behind the scenes, while Stanton and Anthony gave more lectures.

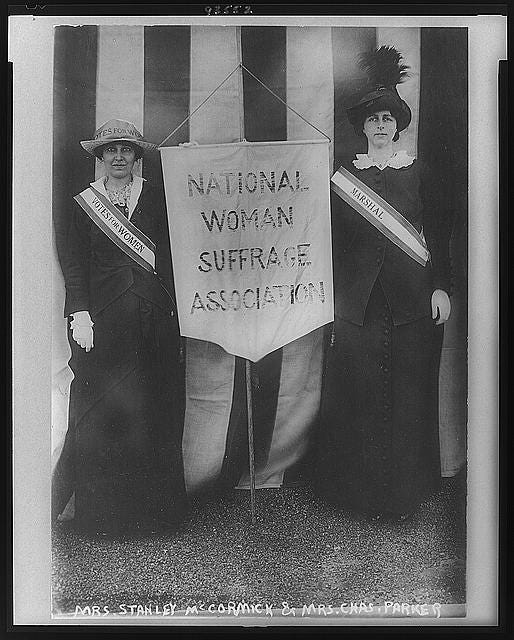

The three women formed the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, and also collaborated in writing three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage.

While other activists focused on women’s suffrage alone, the “Triumvirate” also also pursued other reforms, including an eight-hour work day, equal pay, and greater rights in marriage and divorce.

They also wanted a federal women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution, while other more moderate suffragists (like Lucy Stone) thought that women’s suffrage would be obtained state-to-state.

And the Triumvirate’s approach may have been more radical than others, too.

In 1876, Gage and Anthony stormed the podium at the American Centennial celebration to present the Declaration of Rights of the Women to William Wheeler, the vice president of the US.

In their declaration, Gage and Stanton had written that by denying women the right to vote, the US government was violating the US Constitution.

They argued that women were subjected to taxation without representation, and denied the right to a jury of their peers (as only men could serve as jurors).

And Gage continued to communicate her beliefs through her words – and her actions.

When the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886, Gage protested on a cattle barge in New York Harbor.

She said the female symbol of liberty was “a gigantic lie, a travesty and a mockery” considering women in the United States did not have basic liberties.

So if the Triumvirate worked together for decades, why did Anthony and Stanton get captured by history (and Ken Burns!) while Matilda Gage has been all but forgotten?

Because Matilda Gage was “the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time.”

Gage didn’t just advocate for women to have more rights – she wanted Black Americans and Native Americans to have more rights, too.

In 1862, she gave a flag presentation speech to soldiers heading off to fight in the Civil War, and argued the war was not about preserving the Union (as President Lincoln had said), but about ending slavery.

“Unless liberty is attained – the broadest, the deepest, the highest liberty for all, – not for one set alone, one clique alone, but for man and woman, black and white, Irish, Germans, Americans, and negroes, there can be no permanent peace,” she said.

She also criticized the federal government’s treatment of Native Americans, and wrote about her admiration for Native American groups who treated women and men equally.2

And she felt that organized Christianity oppressed women, writing:

“The most stupendous system of organized robbery known has been that of the church towards woman.”

Her open criticisms of both religion and the government put her at odds with many suffragists – including Anthony.

And in 1889, when Anthony merged the National Woman Suffrage Association they co-founded with the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association, Gage left in protest.

Anthony felt the vote was the sole issue of importance, where Gage and Stanton felt it was only one example of women’s oppression that needed to change.

Stanton and Gage also shared similar views about how religion oppressed women — in great contrast to the conservative members of the American Woman Suffrage Association.3

But when Anthony merged their associations, Stanton did not leave with Gage.

Anthony made Stanton an offer she couldn’t refuse — the presidency of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

Anthony (and her biographer Ida Husted Harper) would go on to write that the merger was accomplished “in the most thoroughly official manner, according to the most highly approved parliamentary methods.”

She wrote that “the final result was satisfactory to a large majority of the members of both societies, who since that time have worked together in unbroken harmony.”

But in private correspondence, Gage described the situation differently.

She called Stanton a traitor (specifically, Benedict Arnold) – but saved her harshest words for Anthony, whom she felt had “destroyed” their movement.

Anthony’s newly-formed association adopted the state’s rights strategy which brought segregation, Jim Crow laws, and a focus on suffrage for white women instead of all women.

Gage went on to form the Woman’s National Liberal Union, dedicated to “challenging the religious mandate of women’s submission to men” and “halting the encroachment of religion in politics.”

And she continued writing.

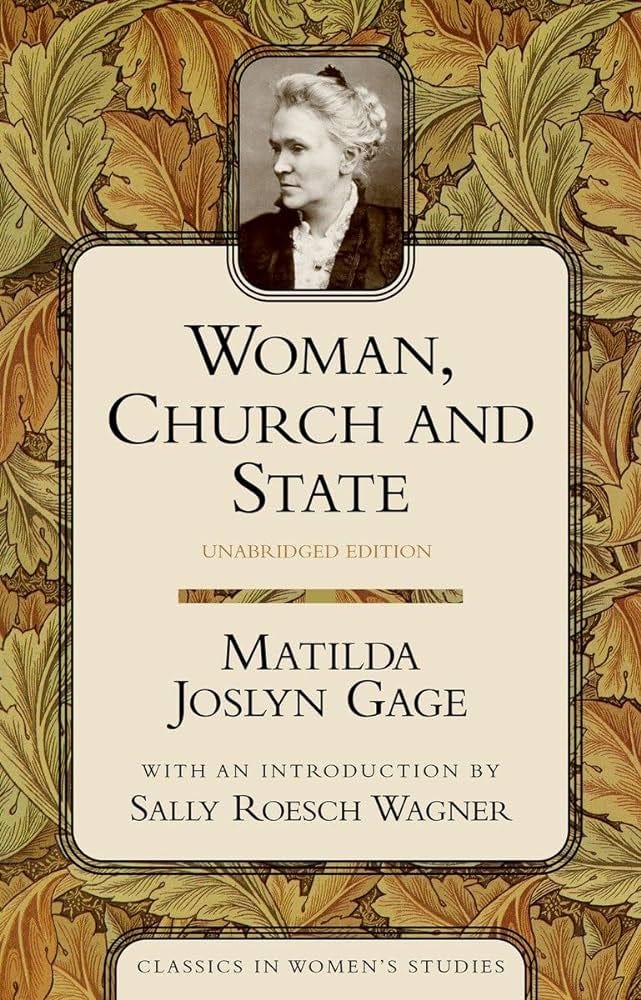

Her magnum opus, Woman, Church and State, was published in 1893.

It detailed the injustice and discrimination women experienced due to Christianity and the evolution of the Western state.

When Gage died five years later, on March 18, 1898, the New York Times called her “one of the earliest champions of woman’s rights in America.”

Her gravestone in Fayetteville, New York carries one of her lifelong mottos4:

“THERE IS A WORD SWEETER THAN MOTHER, HOME, OR HEAVEN — THAT WORD IS LIBERTY.”

But Gage’s role in women’s rights and the suffrage movement was diminished over the next few years, as both Stanton and Anthony outlived her.

After Stanton’s death in 1902, the next volume of History of Woman Suffrage was edited by Anthony – and her hand-picked biographer, Harper.

And history, as Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner wrote in The Women’s Suffrage Movement, “is written through the lens of the author.”

The final three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage – completed by Anthony and Harper – “smoothed out some of the rough edges of the movement” and “toned down the radical edge.”

And Anthony’s version of the story – repeated by historians for more than a century – downplayed Gage’s role and contributions.

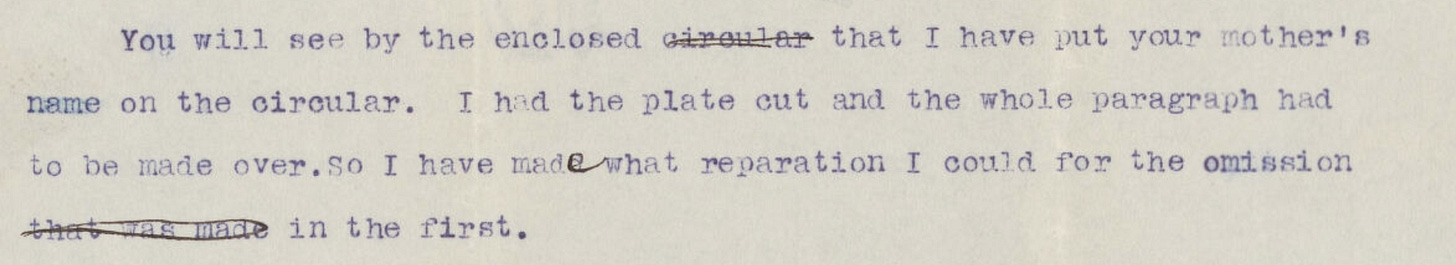

Gage’s children – who knew Anthony – complained to her when they saw their mother’s role diminished.

Anthony downplayed it as an oversight.

After Stanton passed away, Anthony continued editing the final versions of The History of Woman Suffrage.

She then burned many of her papers and letters, thus ensuring that The History of Woman Suffrage would stand as the only “insider” account of the movement’s early years.

And Anthony — having outlived both Gage and Stanton — is often credited as the sole founding leader, and the main author of The History of Woman Suffrage.

Perhaps that explains how Susan B. Anthony got her face on a coin – and how Matilda Joslyn Gage became a footnote.

One more thing…

Matilda Joslyn Gage spent much of her later years living with her daughter Maud and son-in-law, L. Frank Baum.

Baum was a struggling artist when he married Maud, but Matilda encouraged him to publish the stories he told his children.

Two years after Matilda Gage died, he published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, to much success, followed by 13 more Oz novels.

Many biographers of Baum believe he was influenced by Matilda’s ideas about female power, and the ideas she shared in Woman, Church and State.

Still Curious?

For more about the history of women’s suffrage, check out Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner’s book, The Women’s Suffrage Movement.

Wagner is also the founder of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation and THE expert on Matilda Joslyn Gage.

I am so thankful to Dr. Wagner, who generously spoke to me about her research, and for sharing her vast knowledge of Matilda Joslyn Gage with the world.

Our conversation made me even more curious about the people and stories that haven’t been captured adequately by the history books.

And, she reminded me that the people and stories we “know” often require further examination.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

If you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap massive rewards – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Stay Curious!

-Beth

Quick Language Point: Suffragist is the term used to describe women who were fighting to gain the right to vote in the US. Suffragette is the term used in England.

Matilda’s advocacy for Native Americans’ rights would see her honorarily adopted into the Mohawk Nation’s Wolf Clan in 1893. She was given the Wolf Clan name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi, meaning “She who holds the sky.” There is a whole other story to be told - and luckily Dr. Wagner has written it.

How different were these woman suffrage associations? Well, the American Woman’s Suffrage Association had also joined forces with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, an organization that sought woman suffrage in order to create a Christian nation.

This motto is a riff on the title of a 19th-Century collection of pious poems and stories, Mother, Home and Heaven.

Hey, Beth. Here’s another of those little known suffragists: https://cattcenter.iastate.edu/home/about-us/carrie-chapman-catt/

Thought you’d appreciate that. Thanks for these pieces. I really enjoy them. Hugs.

Excellent deep dive!