Reading any good books?

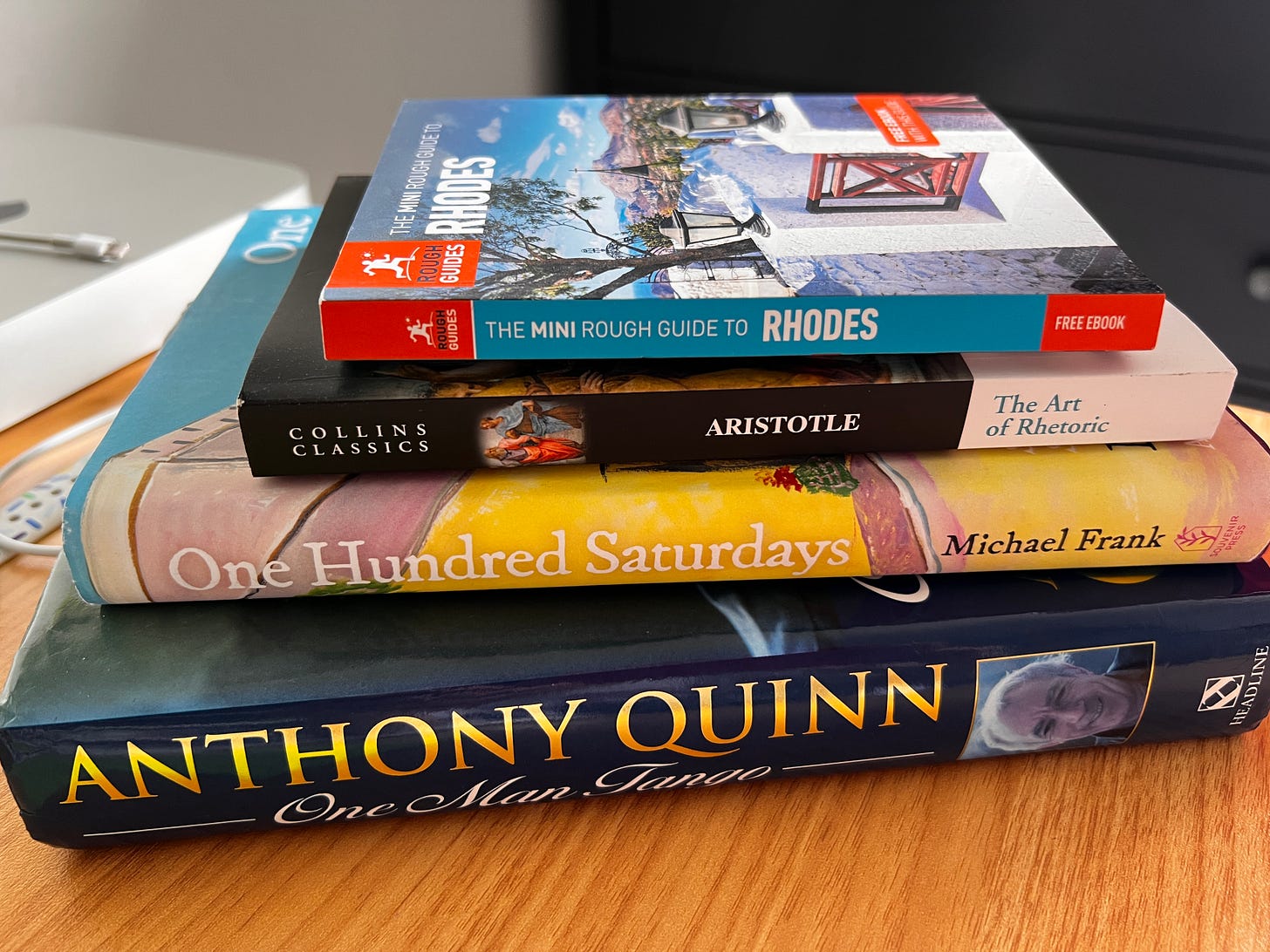

I’m deep in research on Rhodes, Greece as I prepare to run a communication workshop there next month.

As you might expect, my research involves inspiration from a mix of history and pop culture…

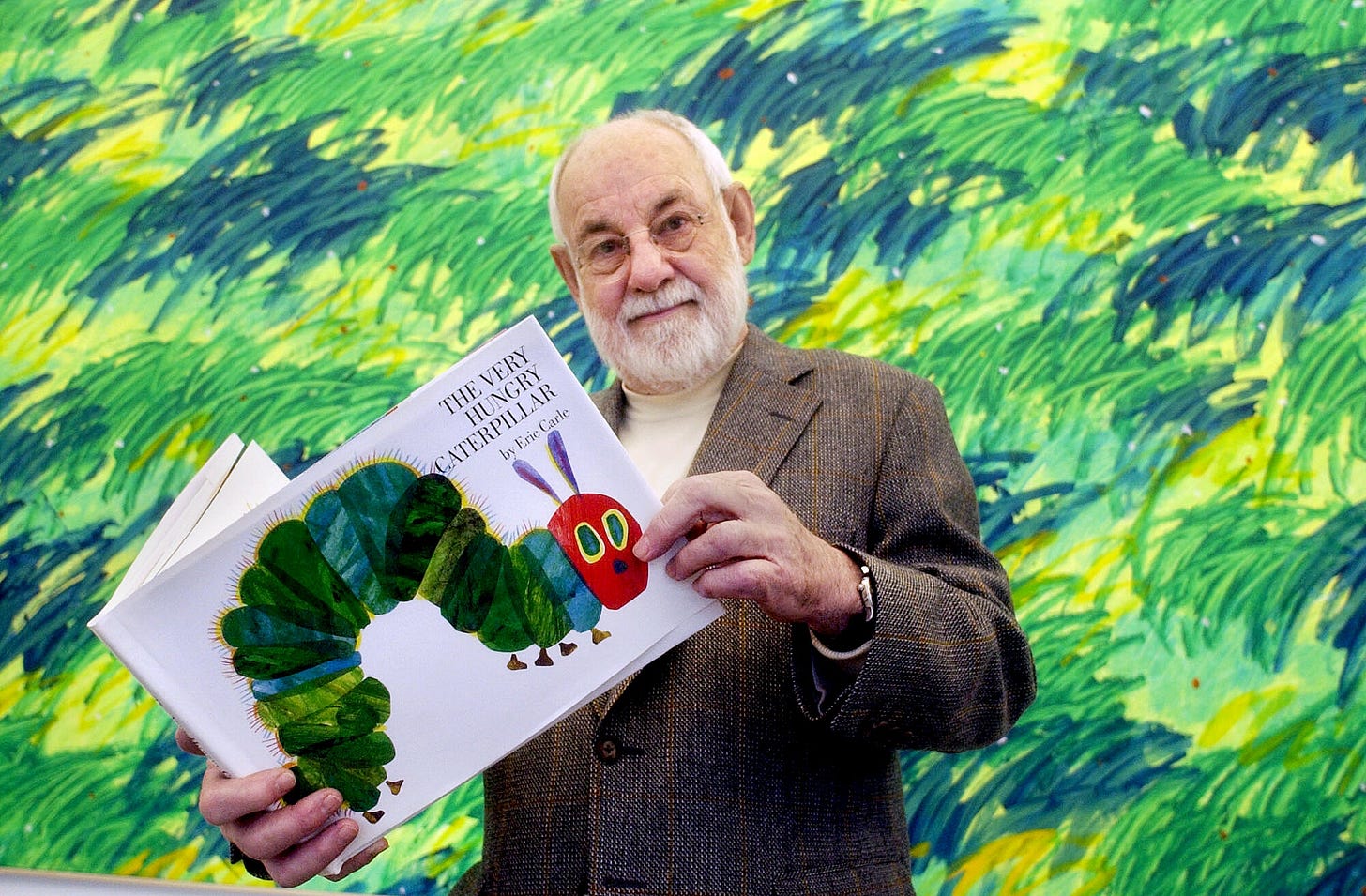

But today I want to share a story about another book — The Very Hungry Caterpillar — and its author, Eric Carle.

Would you believe the 56th anniversary of the book is in just a few days? (June 3rd)1

I imagine you’ve read the book (or are familiar with it) as it’s sold more than 50 million copies and has been translated into 70 languages.

I read The Very Hungry Caterpillar as a child, and to my own children — but I can’t say that I knew anything about the book’s author, Eric Carle.2

But of course, I was curious…

Eric Carle was born in Syracuse, New York in 1929, and his love of nature and art came early.

“When I was a small child, as far back as I can remember, he [my father] would take me by the hand and we would go out in nature,” Carle told The New York Times in 1994.

“And he would show me worms and bugs and bees and ants and explain their lives to me. It was a very loving relationship.”

Carle’s father drew well, and Eric’s artistic talents were recognized early by his first grade teacher, Miss Frickey.

“She told my mother that I had talent, and she told her to nurture it,” Carle said.

But things changed for Eric and his parents in 1935, when family pressure saw them return to Germany.

Carle began school in Stuttgart, and it was drastically different from his experience in America.

It was “very strict” with “small rooms, narrow windows, hard pencils, small sheets of paper, and a stern warning not to make mistakes.”

And things got worse in 1939 when World War II began and Eric’s father was drafted by the Nazis.

He was later captured by the Russians and became a prisoner of war — starved down to 85 pounds, and away from the family for eight years.

Though he survived, Carle said his father returned to the family a “broken man.”

During the war, art class was the highlight for Carle.

Growing up surrounded by “the grays, browns and dirty greens used by the Nazis to camouflage the buildings” only deepened his love for bold and joyful colors.

Eric’s teacher, Herr Krauss, secretly showed him a box of what the Nazis called “degenerate art”, including the banned works of Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky.

“Their strange beauty almost blinded me,” Carle said.

“At great personal risk, my art teacher quietly defied the regime, so that a 12-year-old boy who loved colors, shapes, and lines would be able to experience the wonder of an art he had until then not even known existed.”

Carle would pursue his artistic talents at Stuttgart’s prestigious art school, the Akademie der bildenden Künste.

But he longed to return to America — and in 1952, arrived in New York with his portfolio and $40.

He began working as a graphic designer at the New York Times, and by the mid-1960s was working as an art director at an advertising agency in New York City.

Although he enjoyed the job, he found himself wanting more.

“All too often I had to go out with clients, have dinner and drinks with them, attend meetings, and there was all the backstabbing and office intrigue.3

“It just hit me one day that I wanted to make pictures,” he said.

And then a lobster changed his life.

Or rather, the drawing of a lobster.

In the late 1960s, educator and author Bill Martin Jr. saw a drawing of a lobster in a magazine advertisement Carle had made.

And Martin knew instantly he had found the artist to illustrate his next book.

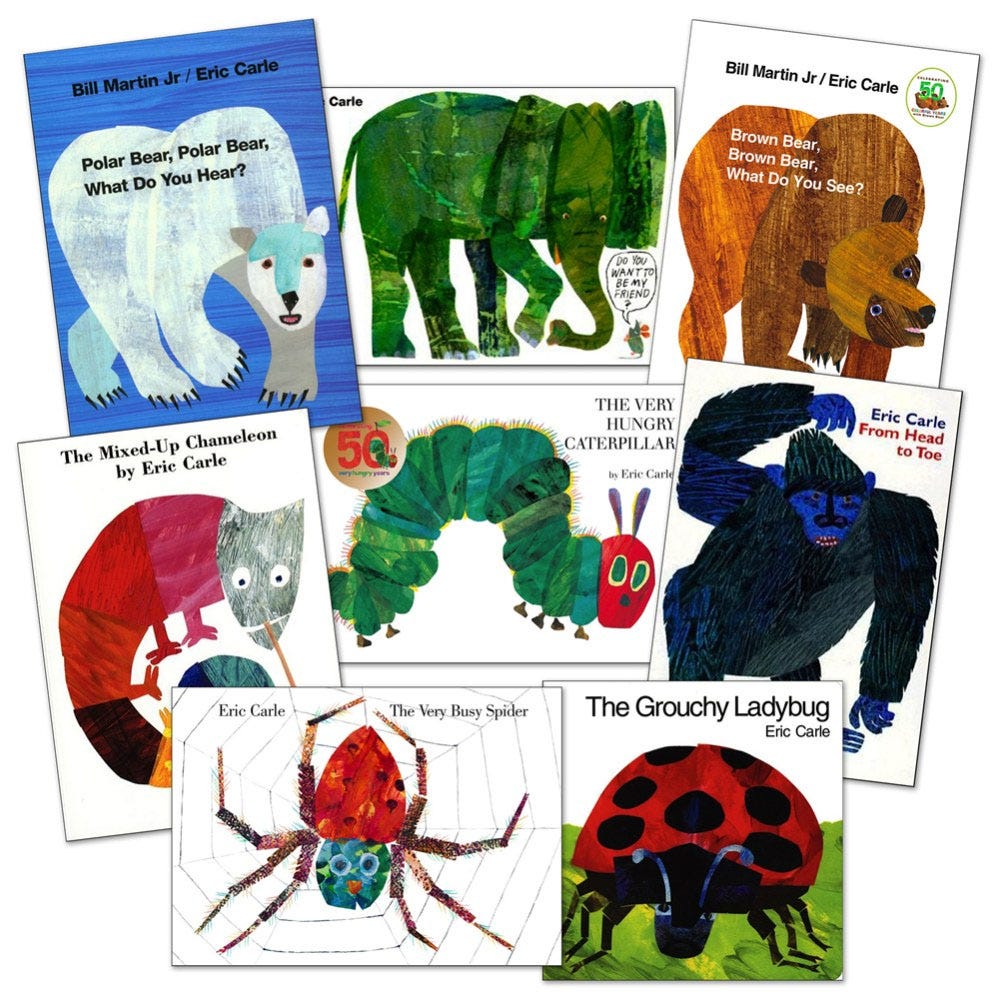

Carle illustrated Martin’s book Brown Bear in 1967 — and the two collaborated for three additional “bear” books.

Then in 1968, Carle created his first solo picture book: 1, 2, 3 to the Zoo.

And then one day in 1969, Eric Carle was bored.

He took a stack of paper and a hole-punch and playfully punched holes.

He wasn’t trying to write a book at that moment, but when he looked at the papers with holes punched in them, it gave him an idea.

“Straight away I thought of a book worm,” he said.

He wrote a children’s story about a gluttonous worm named Willi, who ate a lot, felt sick, and then went to sleep.

But the story didn’t really have an ending.

Carle took his idea for ‘Willi the Worm’ to editor Ann Beneduce.

She knew the picture book genre well, and wasn’t sold on the idea of a book about a worm.

She suggested a caterpillar instead.

That instantly gave Carle the idea for a butterfly — and an ending for a story of transformation that would become The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Carle’s creative idea of punching holes in the pages of a book (and thus turning a book into a toy) was different, but it led to a major problem when it came time to get the book printed.

“I couldn’t find anyone in the US who could manufacture this book, with all its ingeniously die-cut pages, and irregular bindings,” Benduce said.

But fortunately for Carle, he had a champion in his editor.

Beneduce was determined to get Carle’s book published, and while visiting Japan, she showed it to Japanese publishers.

One publisher, Hiroshi Imamura, liked it so much he agreed to print it.

The Very Hungry Caterpillar hit shelves on 3 June 1969 — just before Carle’s 40th birthday.

And the simple but everlasting tale —told in just 224 words— would become a huge hit.

And just as the caterpillar transformed, so did Carle’s career.

Although the caterpillar may be his most famous work, over the course of six decades, Carle wrote more than 70 children’s books and sold more than 170 million copies.

“The success of my books is not in the characters or the words or the colors, but in the simple, simple feelings,” Carle told the New York Times in 1994.

“I remember that as a child, I always felt I would never grow up and be big and articulate and intelligent.

“‘Caterpillar’ is a book of hope: you, too, can grow up and grow wings.”

Eric Carle passed away on May 23, 2001 at the age of 91.

One more thing…

If you’re ever in Amherst, Massachusetts, you can check out the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

PSA: My curiosity never takes a vacation — but Curious Minds will be on a brief hiatus for the next few weeks.

Also, I’m trying something new and sending today’s issue out 3 hours later than normal.

Did you notice? Did it hit your inbox at a better time? Does it matter?

I’d love to hear if you have a preference!

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, Stay Curious!

-Beth

Where are my Gilmore Girls fans who know why “June 3rd” is significant?

Perhaps that’s because I wasn’t digging through the card catalog and microfiche when I was reading this book as a child…

Hmm…I imagine my friends who work in advertising could relate to this!

I love this! My sister was part of Eric Carle's editorial team in the early 2000's; one of my few six-degrees-of-separation claims to fame. :)

This hit: “‘Caterpillar’ is a book of hope: you, too, can grow up and grow wings.” Thanks for your curiosity, as always, Beth x