Hello!

I love learning, but in the last year I’ve had to learn about things I never thought I’d learn about —

Like repointing bricks.

The secondary school process in London.

(Don’t ask).

And…kitchen design.

And that brings us to today’s story.

When I went to my first kitchen store in London, the salesman asked:

“Do you want an English kitchen or a German kitchen?”

This was not a decision I was aware I’d need to make – nor did I know the differences between the two.

So I did what I normally do – started researching.

And as I was researching German kitchens, I came across an article about “The Frankfurt Kitchen.”

I had no idea what that was either.

But of course, I was curious…

Have you ever been in a kitchen that had a window over the sink, well-organized cabinets, or an easy-to-clean tiled backsplash?

Then you’ve likely been in a kitchen inspired by The Frankfurt Kitchen.

And the person in charge of designing the Frankfurt Kitchen was an Austrian architect named Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky.

Born in Vienna in 1897, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky defied expectations by becoming the first female student at the Kunstgewerbeschule (the University of Applied Arts Vienna today).

Although Schütte-Lihotzky came from a liberal family, they did not encourage her studies, thinking she would “starve to death.”

“In 1916, no one would have conceived of a woman being commissioned to build a house – not even myself,” Schütte-Lihotzky said.

During her studies, Schütte-Lihotzky focused on designing affordable housing for the working class.

But she had grown up in a bourgeois family – and did not know much about how the working class lived.

So her professor encouraged her to visit working class housing — and Schütte-Lihotzky was shocked by the living conditions.

“I didn’t yet know the great Heinrich Zille quote, ‘You can kill a person with an apartment just as well as with an axe,’ but I felt it,” Schütte-Lihotzky would later write in her memoir.

After World War I, Schütte-Lihotzky designed apartments for single, working women, and then complexes for veterans.

Her designs saw her winning awards, and caught the attention of German architect and urban planner Ernst May.

In 1926, May invited her to be part of the “New Frankfurt” project he was leading – designing modern, functional, affordable housing in Germany.

She was the only woman in the team, and her role was to design an area that had long been ignored by architects – the kitchen.

The kitchen was the domain of women and servants – and viewed as unworthy of an architect’s expertise.

Some may have assumed Schütte-Lihotzky was tasked with the kitchen design because of her experience, but she actually had very little knowledge of cooking or the kitchen.

So she read the works of American home economist Christine Frederick, who had studied how to make kitchens more efficient for women.

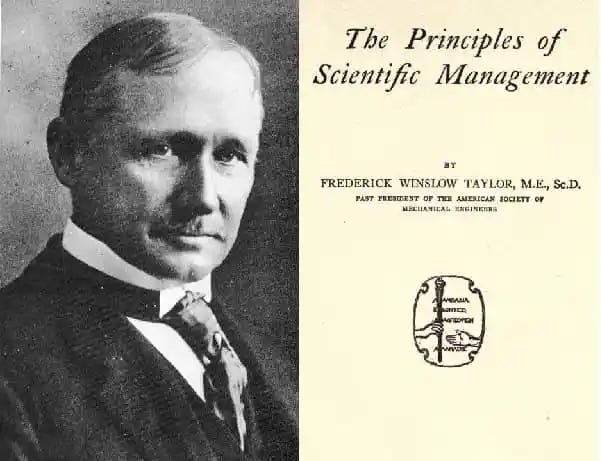

She also read Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management1, that analyzed and synthesized workflows.

And she interviewed housewives and other women, and observed them working in kitchens, conducting her own time and motion studies to better understand their needs.

She looked at the kitchen project as an architect – with a goal to make life easier for those using it.

She felt that if she could make work in the kitchen more efficient, it would leave women with more time to explore intellectual pursuits and leisure activities.

The kitchens she observed in working-class homes were built within the living room, which often was also used as a bedroom.

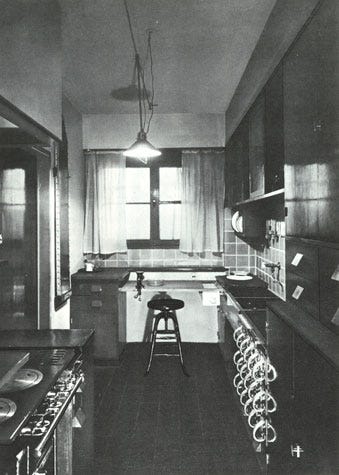

Schütte-Lihotzky wanted to separate the kitchen into its own space, and studied the kitchens of railway cars and ships, looking at ways to maximize space and efficiency.

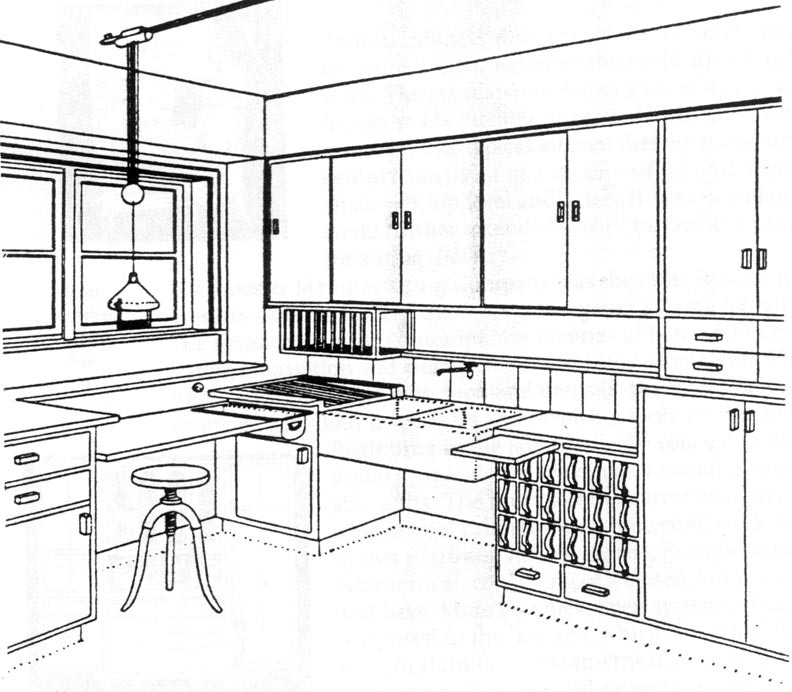

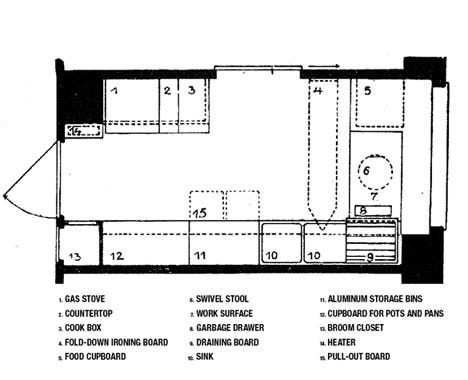

Her kitchen was small – just 13 feet long and seven feet wide – and she used Taylor’s scientific management theories to minimize the steps housewives had to take between tasks.

She carefully thought about not just the most efficient designs, but also the building materials.

Oak was used for the flour containers (to repel mealworms) and beech was used for cutting surfaces (to resist staining and knife marks).

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchen was a groundbreaking design.

It revolutionized the kitchen for working class people with its introduction of well-organized cabinets, built-in storage bins for dry ingredients, and a double sink that meant water would no longer have to be hauled into the house to wash dishes.

It also included features like a fold-down ironing board, a removable garbage drawer, and easy-to-clean backsplash and countertops.

Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchen was mass produced and installed in more than 10,000 public housing units in Frankfurt by 1930.

And though she didn’t always receive the credit, her designs were celebrated at the time.

The Frankfurt Kitchen was widely publicized in Germany and beyond – noted as a kitchen designed “by women, for women.”

“It worked well as propaganda back then, but to tell the truth, before creating the Frankfurt Kitchen, I never managed a household or cooked or had any experience in the kitchen whatsoever,” Schütte-Lihotzky said.

But the Frankfurt Kitchen did not change the lives of women exactly as Schütte-Lihotzky had hoped.

Instead of freeing women to explore more intellectual pursuits and leisure activities, Schütte-Lihotzky’s design relegated women to the kitchen.

Her kitchen’s small space was designed for one person only – and instead of being in an open living room space with children and other family members, women were now isolated in a cramped area by themselves.

Cooking was no longer a shared task in the household – and many housewives felt restricted in a cold, clinical space.

Schütte-Lihotzky’s kitchen was built for efficiency – but in removing the social and cultural aspects of cooking, it removed the joy and connection that can be felt in a kitchen.

Schütte-Lihotzky’s space-saving design may not have advanced women in the ways she hoped, but it would go on to influence kitchen plans in Europe and the US.

And many of the elements of modern kitchen design take inspiration from the designs she made nearly a century ago.

So if Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky had such an influential design, why isn’t she more well-known?

In 1939, Schütte-Lihotzky joined Austria’s Communist Party, and was later arrested by the Gestapo.

She narrowly escaped a death sentence, and would have served 15 years in prison had she not been liberated by US troops in 1945.

She returned to Vienna after the war ended, but her strong political views prevented her from receiving any major public commissions2.

“In twenty years, I built two kindergartens, while former Nazis had very large orders,” she said.

Instead she consulted on projects in China, Cuba, and the German Democratic Republic.

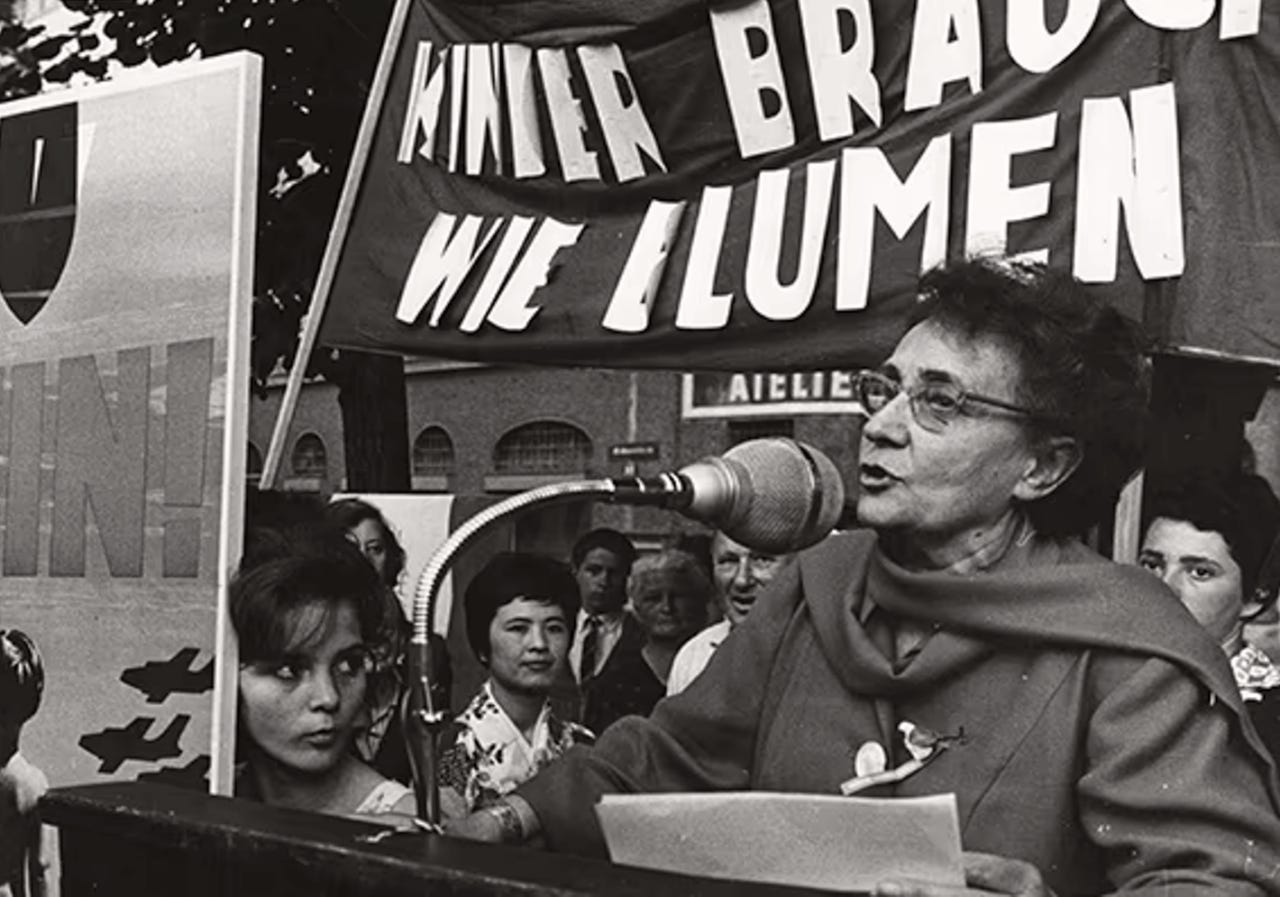

She dedicated her life to improving social housing, and was a prominent activist who advocated for peace and the women’s movement.

But her work with the Frankfurt Kitchen came back in the spotlight in the 1980s.

She began to receive public recognition for her work throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Even Ikea presented her with an award.

But instead of embracing the recognition, she seemed to resent that her life was reduced to a kitchen.

“I am not a kitchen,” is one of her most famous statements.

“I’ve done a lot more in my life than just this!” Schütte-Lihotzky told a reporter in 1997.

A few years later, when she was 101, she repeated those sentiments, saying:

“If I had known that everyone would keep talking about nothing else, I would never have built that damned kitchen!”

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky died in 2000, just before her 103rd birthday.

But her kitchen design lives on…

In 1990, a scale model of the Frankfurt Kitchen was put on display in Vienna, and other models have been displayed in museums across Europe, the UK3, and the US.

And I will think of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky when I get my German kitchen installed later this year (which thankfully, will be in a space larger than her original design!).

One more thing…

Like that kitchen? Take it with you!

Here’s another fun fact about kitchens and Germany:

In Germany, it’s common for homeowners to take their kitchens with them when they move, as many homes are sold without a kitchen.

In fact, I was told a German kitchen is designed to be moved eight times!

Even rental properties often come without a kitchen.

I wonder how many people (unfamiliar with this custom) check out an apartment in Germany, sign the lease, and then are shocked to move in and find the kitchen gone.

Heading to Vienna?

You can visit the apartment where Margarete lived the last 30 years of her life.

The Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky Club, an independent association founded in 2013, had Margarete’s 55 square meter apartment in Vienna reconstructed in 2021-22.

Visitors can now experience the apartment (and its 25 square meter roof garden) the way Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky would have.

It also features original furniture, including lamps, curtains and tables.

And the kitchen was meticulously reconstructed, too.

And while in Vienna, you can view a replica of the Frankfurt Kitchen in the MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna.

More thoughts on curiosity!

What Do You Know to Be True?

Roger Kastner asked me this question for his podcast of the same name.

Curious what I know to be true?

Check out our conversation: “Following Your Curiosity to Find Truth and Joy with Beth Collier” on YouTube, Apple Podcasts, or Spotify.

And speaking of curiosity…

I had the opportunity to chat all things communication and curiosity recently with Katie Macaulay on The Internal Comms Podcast.

Have a listen and find out how my high school’s motto inspired me — and what I learned from all those high-flying execs I encountered when I was photocopying (and faxing) their documents in Hollywood.

You can listen to our conversation on Spotify or Apple podcasts.

How Can I Help?

I’ll keep saying it: Communication matters.

And if you want to improve your communication (and get all the good things that come with that), I’m your gal.

So many companies could reap significant benefits – from performance and culture to retention and engagement – by improving their communication.

So, if you know someone who could benefit from some help (as even the most seasoned leaders do), please get in touch and check out my website for more information.

You can also see my Top 10 list of what I can (and can’t) do for you here.

And if you see any communication examples (the good, the bad, and the ugly) that you think are worth analyzing or sharing, please send them my way!

Until next time, stay curious!

-Beth

Another place you’ve seen Taylor’s scientific management theories in action? McDonald’s.

Sexism likely played a part, too.

Sadly, London’s V&A Museum does not currently have their Frankfurt Kitchen on display.

Totally unaware of this, fascinating.

While we're talking kitchens, allow me to recommend Scandinavian comedy Kitchen Stories. Delightful film about a Norwegian bachelor farmer agreeing to have an ergonomics expert watch him use his kitchen as part of study to improve kitchen design.

Absolutely LOVED this! Soooooo interesting, thanks for revealing all this good stuff! If you ever get the chance to go to Farley’s - the house where Lee Miller lived

Near Lewes - her kitchen is all exactly as she left it.

Apparently she was one of the first people in the UK to get a fitted kitchen…